Music ∷ Sam Porter

Show Artwork ∷ Nikolaos Pirounakis

Episode Artwork ∷ Lily Meek

There was one package film left in production at the end of the 1940s, and it would turn out to be far-and-away the best of the bunch. It combined two unrelated stories with hardly any connective tissue at all, other than being based on literary classics, and yet both were strong enough to actually complement one another rather than detract. One half would be a long-in-development adaptation of a British children’s classic, and the other a recent project based on a beloved American short story that had entered into folklore. The package film format at Walt Disney Productions was about to come to an end, and it would go out on one hell of a high.

The open road! The dusty highway! Come!

I'll show you the world! Travel! Change! Excitement!

'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' was an attempt to salvage the work on two separate projects - an adaptation of Kenneth Grahame’s 'The Wind in the Willows', and another of Washington Irving’s 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow'. Not only were the two stories very different in texture and tone, but likewise were the two sequences. Much of this can likely be explained by their histories - 'The Wind in the Willows' had been in development since 1940, while 'Sleepy Hollow' had only been in development a few years.

While most other films in the Disney canon (even the other package films) have some sort of consolidated history on their creation, there has never been a substantial one produced for 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad'. These notes use a number of different sources to try and tell the story of the making of this film, one that involved many of the greatest artists at the studio over the course of a decade, running concurrent with the giddy success of Snow White, the financial woes that followed it, the strike in 1941, the ultimatum from Bank of America, the Second World War, the company restructuring and the creative chaos of the package films. In many ways, no other film from the Wartime Era better represents the shift from the glory of the Golden Age to the classics that were to come - the Disney Animation that was and the Disney animation that was to be.

Here is the story of 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad', perhaps the great forgotten gem of Disney feature animation.

Without good stories, we cannot make good pictures. Without well-prepared stories, we cannot make the pictures effectively.

He knew though that, for his grand plans to work, the process needed to be streamlined. 'Snow White' had very much been made in the dark, every artist in every department attempting something that hadn’t been done before, and even though the final product was sublime, the process had been chaotic. In 1937, Walt established two new departments at the studio, both of which would help consolidate the development process before a project began production, to try and avoid the years it had taken to develop the story on 'Snow White'. The Character Model Department, headed by Joe Grant, would be in charge of character design and story development, while another department, the Story Research Department, headed by artist John Clarke Rose, would find the stories they would be telling.

The path to a picture in production is strewn with unforeseen pitfalls. In the past, many of our short subjects ran into unexpected snags which made it necessary to shelve the picture indefinitely or tear it down and rebuild it, or push through with a prayer. Much of ‘Snow White’ was tossed out in mid-production. ‘Pinocchio’ had been under way for several months when glaring errors appeared, necessitating a complete overhaul. As a form of insurance against these hazards, Walt has been developing a unique research laboratory whose most important function is to discover and eliminate story weaknesses in advance of animation production.

The role of the department was to read hundreds of stories and novels, provide synopses for them and, for those properties of interest, pursue and secure the film rights. In 1938, flush with the success of 'Snow White', Rose facilitated an enormous rights spending spree, acquiring 24 properties. Some, such as 'Peter Pan', 'Winnie-the-Pooh' and the 'Uncle Remus' stories, would form the basis for future films. Others give us a clue into the projects that could have been, including 'Don Quixote' and 'The Rubaiyat of Omar Khayyam'. They even acquired the rights to John Tenniel’s illustrations for 'Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland'.

One novel included in this spending spree was Scottish writer Kenneth Grahame’s 'The Wind in the Willows'. Grahame’s son Alistair had been born premature in 1900, and as a consequence was plagued with serious health problems throughout his life, including blindness in one eye. When Alistair was four, Kenneth Grahame began telling him bedtime stories about the adventures of a Toad and his friends Rat, Badger and Mole, living along the bank of the Thames. Over the years, he would continue to expand on the stories through letters to Alistair when Grahame was away, and in 1908, after retiring from the Bank of England, he consolidated the stories into 'The Wind in the Willows'. It received mostly negative reviews upon publication, but was ecstatically embraced by the public, and became a huge success and an instant classic.

Walt Disney had been first introduced to 'Willows' in 1934, when he was given a copy by British correspondent Lady Carlisle, and he was encouraged by others to adapt it, who thought the anthropomorphised animal characters would be a great match for animation. There was some early movement, with Gustaf Tengren and Albert Hurter completing some rough character studies in the 30’s, and Wilfred Jackson initially being assigned the project as director, until he was taken off the project to direct 'Night on Bald Mountain' in 'Fantasia'. Despite this work though, and the studio library holding multiple copies of both the novel and A.A. Milne’s beloved stage adaptation 'Toad of Toad Hall', Walt was unenthusiastic about the novel, and instead focused on 'Alice in Wonderland'.

One person who was enthusiastic about the idea of adapting 'Willows' was artist James Bodrero. Joining the studio in 1938 after working as an illustrator, Bodrero had become a key member of the Character Model Department, and had created extraordinary development artwork for 'Fantasia' and 'Dumbo', as well as travelling with the Goodwill Tour to South America in 1941. The year prior, he approached Walt with the idea of turning 'The Wind in the Willows' into a feature, which took a lot of convincing.

I had read the book. I wanted to do it, a long time before Walt. Walt thought it was awful corny, but we finally got him around to it.

Bodrero began working with fellow Character Model Department artist Campbell Grant on the storyboards for the film. In the process, they developed a revolutionary new technique for enhancing the Leica reels. Since the early days of the sweatbox sessions, the storyboards had been shot with a Leica camera and assembled as a story reel, or Leica Reel, accompanied by recorded dialogue. In the past though, the pacing had been dictated by the images, not the recording. Bodrero and Grant decided on the opposite approach, syncing the images to the recording instead, which featured their own voices as all the characters.

The results, which more closely emulated a finished film, were a huge success, receiving a burst of applause from its first audience at the studio. Walt would later show the reel during his pitch presentation for U.S. Government contracts in April 1941, and the method is still the industry standard to this day. As well as working on the project over the next nine years, Campbell Grant would also provide the final vocal performance of Angus McBadger, thanks to his strong skill with accents.

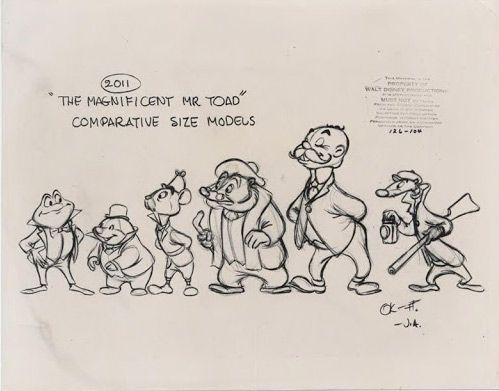

Around the same time, artist Mel Shaw, who had just finished conceptual work on 'Bambi' and 'Dumbo', was assigned to the project. “'Wind in the Willows' was a wonderfully whimsical subject,” Shaw wrote in 2016, “and I especially enjoyed the eccentric “Mr. Toad” portion of the book. I worked very closely with Larry Morey, who was a fine story artist as well as a lyricist for many Disney soundtracks. As we began to develop these creatures from the English countryside, we found that caricaturing our subjects with a British demeanor was interesting animation. The flamboyant “Mr. Toad” had his close comrades, “Ratty,” “Moley” and the conservative “McBadger,” all in a dither during most of the story. I worked on the storyline for about eight months before it was ready to be turned over to the animators.” Retta Scott also worked on character designs for the Weasels.

The adaptation being conceived retained the basic structure of Toad’s escapades - his obsession with motor cars, his imprisonment and escape, and his battle with the weasels for Toad Hall - but differed in tone to Graham’s novel. The book had a melancholy, almost mystical quality, while the Disney version would shift towards madcap antics and broad comedy. There were also early attempts to include music, including the song 'Merrily On Our Way (To Nowhere In Particular)', with music by Frank Churchill and Charles Wolcott, and lyrics by Larry Morey and Ray Gilbert. Written before Churchill’s death in 1942, it remains in the final film.

Despite Walt’s misgivings on the subject, work was progressing nicely on 'The Wind in the Willows', with James Algar stepping in as director. In May 1941 though, production stalled. With the strike in progress, Walt transferred the artists working on 'Willows' to other projects now in need of more manpower, and 'The Wind in the Willows' was left in limbo. It would be many, many years before work would continue.

'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow' first appeared in American writer Washington Irving’s beloved collection of short stories and essays 'The Sketchbook of Geoffrey Crayon, Gent.', which was published over seven volumes from 1819 to 1820. 'Sleepy Hollow' was part of the sixth instalment, published in March 1820. It tells the story of schoolmaster Ichabod Crane, newly arrived in the small New York State hamlet of Sleepy Hollow, his courtship of local coquette Katrina Van Tassel, his rivalry for her affections with Bron Bones, and his horrifying encounter with a Headless Horseman. Along with Rip Van Winkle, it is the most popular of Irving’s short stories, and has become such a staple of American literature that it has practically entered folklore.

Irving wrote the story while living in England, and may have been influenced by European legends of headless horsemen. In these legends, their victims were often proud, arrogant persons who ignored the warnings of these bloodthirsty apparitions. He also drew upon the histories of the Revolutionary War, such as the German soldiers, known as Hessians, who assisted the British armed forces. There were stories of a Hessian soldier found dead and headless after a skirmish in Sleepy Hollow, a village in Westchester County, New York, who was buried in an unmarked grave by the Van Tassel family. Irving had even borrowed the name Ichabod Crane from an army captain he had met while aide-de-camp to the Governor of New York in 1814.

Unlike 'The Wind in the Willows', whose development can be charted from published anecdotal accounts, there is very little publicly accessible material on how Walt Disney Productions came to decide on 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow' as a potential project. Formal production appears to have begun in 1946, when Jim Bodrero submitted story notes for the project.

One clue though may come from another of the package films, 'Melody Time'. Two of the sequences from that film, 'The Story of Johnny Appleseed' and 'Pecos Bill', had originally been intended for an anthology film on American folktales. It is possible that 'Sleepy Hollow' was originally considered as part of this anthology, though as multiple sources suggest it began development as a feature project, it may have been deemed too long compared to 'Johnny Appleseed' and 'Pecos Bill'.

As with many Disney projects of the period, Mary Blair had a huge influence on the look of the film, submitting a number of concept art pieces as well as potential costume designs. The final sequence carves very closely to Irving’s story (including Ichabod’s love for food), but unlike 'The Wind in the Willows', the story is driven almost entirely by music, recounting Ichabod’s escapades as a series of light swing numbers. This suggests that the film entered final production much closer to the 1949 release, and after Bing Crosby was approached to be the narrator. The songs were written by Don Raye and Gene de Paul, and are performed by Crosby and Jud Conlon's Rhythmaires.

Regardless of its original intentions, it became clear that 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow' was not substantial enough to support a feature, and would need to be matched with another property before release. The question was, which would be the right fit?

With the studio now distracted by the war effort, work on 'Willows' moved sluggishly. Over Thanksgiving, Walt reviewed the work and found it inadequate, shelving the project once again. He shifted focus onto 'Peter Pan', but that project soon stalled as well.

The idea of combining 'The Wind in the Willows' with another project appears to have first been broached the following year. After the failure of 'Victory Through Air Power', Walt approached Roy with the idea of pairing 'Willows' with 'The Legend of Happy Valley', the retelling of 'Jack and the Beanstalk' with Mickey Mouse that had begun production before stalling in 1941, or even 'The Gremlins', which was still being worked on despite endless story problems. Roy refused though - the budgets could not exceed $450,000 without putting the company at risk, making such projects impossible.

In 1946, with the studio now returning to commercial-driven projects, shelved ideas began to restart again as potential material for package films. Walt assigned animator Frank Thomas, who had recently returned from service in the war, to co-direct additional material for 'Willows' with original director James Algar. He wanted to salvage what work had been done, but ordered Thomas and Algar to keep it under 25 minutes. When the studio was hit with another series of lay-offs in August 1946, the project was shelved once again. A few months later, development began on 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow', with Jack Kinney and Clyde Geronimo assigned to direct.

'Willows' was revived once again, and the idea was again floated to combine it with other properties, this time with both 'Happy Valley' and 'The Gremlins', under the title 'Three Fabulous Characters'. When The Gremlins still proved impossible to crack, it was dropped and the name changed to 'Two Fabulous Characters'. Soon after though, it was decided that 'Happy Valley' would be a much better match for 'Bongo', another long-gestating production, and the pair were released as 'Fun & Fancy Free' in 1947.

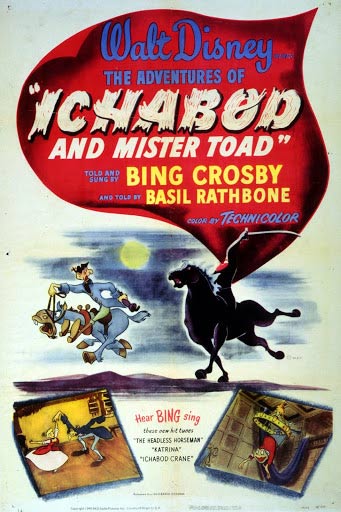

It was at this time that 'The Wind in the Willows' was finally paired with 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow', still under the title of 'Two Fabulous Characters'. An early idea had the film as a pseudo follow-up to 'Fun & Fancy Free', with Jiminy Cricket introducing the stories, but this idea was scrapped. In an interview with Michael Barrier and Milton Grey in 2015, Clyde Geronimo mentioned another framing device that was considered, “to have the Crosby kids, and [Bing] Crosby, in live action at the start, with the kids going off trick-or-treating”. Instead, a live-action framing device set in a library was shot, with 'Willows' narrated by beloved British actor Basil Rathbowne and 'Sleepy Hollow' narrated and performed by Bing Crosby. It was hoped that their popularity would be a drawcard for audiences, though Geronimo wasn’t happy with Crosby’s involvement. “I was sorry Crosby did the narration for it,” he also said in 2015. “Walt thought that maybe he would plus it, by having his name on it, but it was too much Crosby. I think it would have been better to have someone who got more of that Halloween spirit into it... recording Crosby was a little rough. He would say, 'Okay, the take is okay, print it' [after one take]. He ran the show, and I didn't like it.”

You’d get a backlog from the Animators and we’d have to wait and wait and wait for them to send scenes through and when it finally came, it was like a landslide. We’d work all night and stagger out about seven o’clock in the morning. That would happen for days. As long as work was coming in you just got it out!

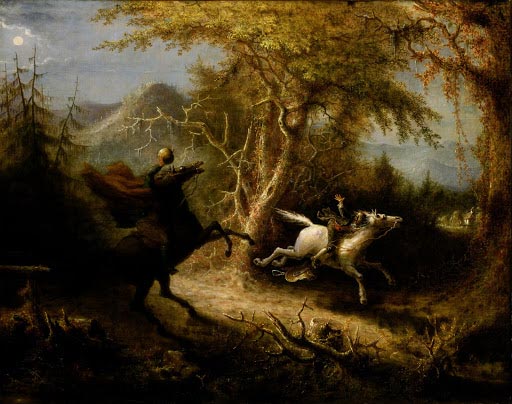

While some of 'Willows' had already been animated over its many years in production, 'Sleepy Hollow' needed to enter production soon, be made fast and on a tight budget. In some cases, animation was recycled from previous films, including the 1937 short 'The Old Mill', and the designs for Katrina Van Tassell were reused from The Martins and McCoys sequence in 'Make Mine Music'. The results though were still breathtaking, with Wolfgang Reitherman and John Sibley animating the incredible chase sequence with the Headless Horseman. Vaudevillian Gil Lamb was used as the live action for Ichabod, and would later do the same for Elliot in 'Pete’s Dragon' (1977).

After (especially in the case of 'Willows') many years of work, the two sequences were finally completed, with a score composed by Oliver Wallace. When the narration was recorded, the production was still called 'Two Fabulous Characters', as evidenced by the reference to the title in the final film. At some point before release though, Walt changed the name to 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad'.

The Observer was less complimentary, C.A. Lejuene writing that he found 'Sleepy Hollow' “sometimes gruesome, on the whole rather commonplace”, and compared Walt to Mr. Toad, saying he has “gone lusting after strange contraptions, and neglected the homely things he used to know.”

Specific criticisms were all over the place. While many agreed that 'Sleepy Hollow', despite some lacklustre moments, had some thrilling sequences, the adaptation of 'Willows' was either an energetic triumph or a lacklustre translation of Graham’s novel. The film did receive one unexpected and unusual honour though - it won the Golden Globe for Best Colour Cinematography in 1950.

The film was never released theatrically again, though like the other package films, was dismantled for parts. It was shown over two episodes, once again called 'Two Fabulous Characters', on the Disneyland TV show in 1955, and then split into two shorts for theatrical release, 'Sleepy Hollow' in 1958 and 'Willows' in the UK in 1967 and the U.S. in 1975. 'Willows' was also later distributed on 16mm to schools in 1980.

Even though it would not be seen in its original form again for many decades, 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' has had a quiet but important legacy. This is one of those forgotten gems that, when discovered by Disney lovers, often comes as a surprise. 'The Wind in the Willows' is a frenetic, hilarious, witty and wonderfully anarchic film, with tremendous character animation, mature and well-considered comedy and a genuine sense of threat and danger. 'The Legend of Sleepy Hollow' features maybe the only attempt at traditional horror in a Disney animated film, with the final chase from the headless horseman ranking as one of the great horror sequences in any film and an unquestionable triumph in animation. When Tim Burton directed his own adaptation of Irving’s story in 1999, he spoke openly about his affections for the Disney film, and included a number of references to it in his own.

'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' is probably the finest Disney film from the Wartime Era. Rather than feeling cobbled together, it is weirdly appropriate that these two stories should sit side by side, and after the chaos of the years following the war, written in every frame of 'Make Mine Music', 'Fun & Fancy Free' and 'Melody Time', there is a confidence to Ichabod and Mr. Toad, a sense of artistic and technical stability. Its lack of theatrical re-releases and the juggernaut arrival of 'Cinderella' the following year may have pushed the film out of the collective consciousness, but this is a film begging to be rediscovered and reevaluated.

And yet this was still an extraordinary period. Across these six films, animation was still evolving, often in imperceptible ways. The South American films may be little more than travelogues, but they opened up Disney animation to new cultures, textures and sounds, and are at times remarkable technical achievements. The Package Films may not rise to the monolithic ranks of 'Fantasia', but beside moments of banality are flashes of imagination and daring, experimentation with new styles and visual languages. And 'The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad' brings the era to a close with a return to traditional storytelling, now imbued with a new sense of anarchy. Most importantly, this era saw the discovery, development and ascension of Mary Blair, one of the most important artists in the studio’s history. Blair cut her teeth on these films, her distinctive hands influencing every single one of them, and in the coming years, her influence on the return to proper feature animation would be monumental.

The films of the Wartime Era may not be of the same stature as 'Snow White' or 'Pinocchio', or even the films to come such as 'Cinderella' or 'Sleeping Beauty', but they are minor classics in their own right, and integral to our understanding of how animation can evolve, and respond and adapt to the world around it. This era also revealed much about the studio’s leader, amplifying the best aspects of Walt’s personality, but also revealing some of the worst. His relationship with the staff and artists had become even more tempestuous, with new staff often leaving in protest of his behaviour and those that had been there for years finding new ways to excuse his bursts of anger, his violent temper and his insane demands. The world itself had also changed. After the war, audiences weren’t interested in the same kinds of films they had been before. They wanted stability, harmony, the good clean American values they had fought for. Walt was forced to be accountable for his actions after the release of 'Song of the South', where his lazy attempt at rewriting American history (whether intentional or not) had revealed a serious conservative flaw in his armour.

He was also starting to lose interest in animation, an art form he had turned into an American institution. There were too many new competitors, and the financial restrictions had forced him to accept what he saw as sub-par work. What was the point of animation if it wasn’t 'Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs'?

As the 1940s came to an end, Walt made one last push to restart feature animation at his studio. He decided to return to what he knew, to the source of his greatest success, in the hopes that it may finally pull them out of the creative quagmire they were stuck in. The films to come would be far more sophisticated than those of the Wartime Era, but would be informed by the discoveries that had been made with them. Over the next seventeen years, Walt Disney Productions would produce an unbroken string of classics, the foundational texts for our understanding of what Disney animation is, and usher in a period of prosperity they had never experienced before. It would also see Walt Disney turn his back on the form almost entirely, distracted by crazier ambitions, and see the artists themselves take creative ownership over the films they made.

Walt Disney Animation was entering its Silver Age.

- Wikipedia for The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, The Wind in the Willows and The Legend of Sleepy Hollow

- Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, Neal Gabler, 2006

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume I - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Golden Age (The 1930’s), Didier Ghez, 2015

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume II - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Musical Years (The 1940’s - Part I), Didier Ghez, 2016

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume III - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Late Golden Age (The 1940’s - Part II), Didier Ghez, 2017

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume V - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Early Renaissance (The 1970’s and 1980’s), Didier Ghez, 2019

- The Disney Studio Story, Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, 1988

- Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, Mindy Johnson, 2017

- Interview with Gerry Geronimo, Michael Barrier and Milton Grey, 2015

- Disney During World War II: How the Walt Disney Studio Contributed To Victory in the War, John Baxter, 2014

- New York Times review of The Adventures of Ichabod and Mr. Toad, October 10, 1949