Music ∷ Sam Porter

Show Artwork ∷ Nikolaos Pirounakis

Episode Artwork ∷ Lily Meek

Now, shall you deal with me, O Prince - and all the powers of Hell!

At the celebration for the newly-born Princess Aurora, the three good fairies Flora (Verna Felton), Fauna (Barbara Jo Allen) and Merryweather (Barbara Luddy) come to bless the baby with gifts. But before they can finish, the evil fairy Maleficent (Eleanor Audley), offended at not being invited, places a curse on Aurora, that on her sixteenth birthday, she will prick her finger on the spindle of a spinning wheel and die. Merryweather dampens the curse so that she will only fall into a deep sleep instead, until true love’s kiss will break the spell, but as extra precaution, the three fairies take baby Aurora to a cottage in the woods and disguise themselves and her, foregoing magic to protect their identity from Maleficent. Sixteen years later, Aurora (Mary Costa) is told of her heritage, and shocked and devastated, is brought back to the castle. Before the sun sets though, Maleficent finally completes her curse, and Aurora falls into a deep sleep. To make sure Aurora will never awaken, Maleficent kidnaps a young man Aurora has fallen in love with in the woods, only to discover, by an extraordinary coincidence, that the young man is Prince Phillip (Bill Shirley), the prince betrothed to Aurora at birth. She locks Phillip inside her castle on the Forbidden Mountain, but the three fairies rescue him, and after a titanic battle where Maleficent surrounds Aurora with a forest of thorns and transforms into a dragon, Phillip defeats Maleficent, awakens Aurora, and they marry, living happily ever after.

As with 'Snow White' and 'Cinderella', the origins of the fairy tale we know as 'Sleeping Beauty' are rooted in European folklore. The earliest versions of the story date back to the 1300’s, but the version we now know originates from Charles Perrault’s 'Stories or Tales of Past Times, with Morals', published in 1697, adapted from a version by Giambattista Basile from 1643. Though the Disney film is credited to the Perrault version of the story, it only adapts the first half, leaving off at the point where the Prince awakens the sleeping Princess. It also resembles the more popular version of the story from the Brothers Grimm from 1812, which streamlines Perrault’s version.

While all Disney animated features until this point had been working from ideas in development since the late 30s and early 40s, 'Sleeping Beauty' was the first project fully developed in the post-war era. Flush with the success of 'Cinderella', the story team at Disney decided to pursue another classic fairytale. In November 1950, Walt Disney announced the start of development on the film, and in 1951, work began on adapting the story, led by screenwriter Erdmann Penner. These early versions attempted to retain the entirety of Perrault’s story, mixing in action sequences for the Prince that had been left over from 'Snow White'. Wilfred Jackson stepped in as director in 1953, and began overseeing the first leica reel, with storyboards shot and dialogue recorded. During that time in 1952, artist Kay Nielsen, who had been one of the primary artists during the Golden Age, returned to Disney, and though he left again a few months later, completed a number of storyboard concepts that would be a guide to the look of the final film.

When Walt saw the reel, he was unimpressed. The team went back to the drawing board, deciding that the better climax for the film would be the kiss that awakened the Princess, and jettisoning the second half. The problem now was that there was no relationship between the romantic leads, who wouldn’t meet until the end. Instead, they condensed the story device that had the Princess sleeping for one hundred years and orchestrated a moment where the two meet in the woods, not knowing who each other are. The Prince they named Phillip, and the Princess they named Aurora, Latin for “dawn”, which was the name of her daughter in the original fairytale and her own in Tchaikovsky’s ballet.

In December 1953, Wilfred Jackson suffered a heart attack, and was no longer able to continue on the project. In a surprising move, Walt appointed Eric Larson, one of the Nine Old Men, as director of the film. It was also at this time that Walt’s ambitions for the film began to form. He instructed Larson that he wanted the film to have a single unifying visual look, to be a “moving illustration, the ultimate in animation”, and though a tentative release date was set for 1957, he told Larson that he didn’t care how long it would take. He also decided that the film would follow in the footsteps of the soon-to-be-released Lady and the Tramp and be developed for the widescreen process. Rather than Cinemascope though, they would be the first to use the Technirama 70mm process, which offered an even wider frame and higher resolution, making it the first animated film ever made for the enormous 70mm format.

'Sleeping Beauty' would also satisfy one of Walt’s great frustrations during the Silver Age. He had been enamoured of Mary Blair’s colour-styling and concept art, but try as they might, the animators could never fully translate her style to the final film intact. What was the point of having such incredible concept artists if the films themselves didn’t reflect their work? 'Sleeping Beauty' would be different. There would be nothing lost in translation, and the Medieval textures that were already being developed for the film would not be diluted by the traditional Disney style. This would not be animation as entertainment. This would be animation as art.

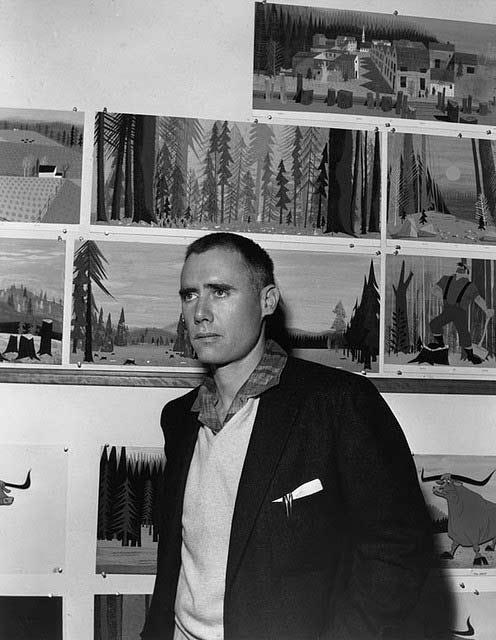

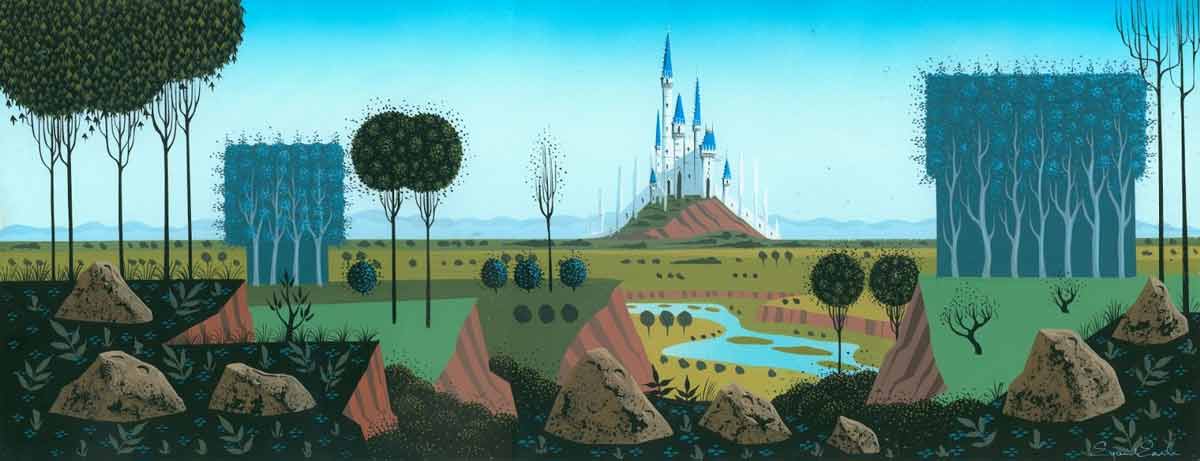

For the first time, Walt Disney handed full creative control of the look of a film over to a single person, not one of his Nine Old Men, but a painter and background artist whose work on Sleeping Beauty would make him a legend in the story of Walt Disney Animation - Eyvind Earle.

For years and years I have been hiring artists like Mary Blair to design the styling of a feature, and by the time the picture is finished, there is hardly a trace of the original styling left. This time Eyvind Earle is styling ‘Sleeping Beauty’ and that’s the way it’s going to be!

Around this time, artist Eyvind Earle began working at the studio as a background painter. Before joining the studio in 1951, Earle had carved himself a modestly successful career as an artist, with works displayed in New York, including the Met. His work had initially leaned towards realism, but while at Disney, he started to develop a style of his own, marrying modernism with medieval or gothic art. His work at Disney began as an assistant background painter on Peter Pan, but he caught Walt’s attention with his background artwork on the Goofy short 'For Whom The Bulls Toil'. He also contributed a number of remarkable background artworks for 'Lady and the Tramp', and was the colour stylist for 'Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom'. With Mary Blair having now left the studio to pursue her own art career, Walt began to pin his hopes for a new holistic Disney visual style on Eyvind Earle.

Walt appointed Earle as the colour stylist on 'Sleeping Beauty', but in a surprising move, declared that he would be the primary visual artist on the film, overseeing every aspect of its look, including the characters and animation. No single artist had ever been given this level of autonomy on a Disney animated feature, but Walt was determined that nothing of Earle’s style would be lost in the final film. He wanted 'Sleeping Beauty' to be a true epic, a complete and overwhelming theatrical experience that demonstrated the full artistic power of animation. This meant that the film could not rely on cute characters and charming whimsy. They needed to elevate their craft so that the artistic possibilities in animation, and in particular Disney animation, would be inarguable.

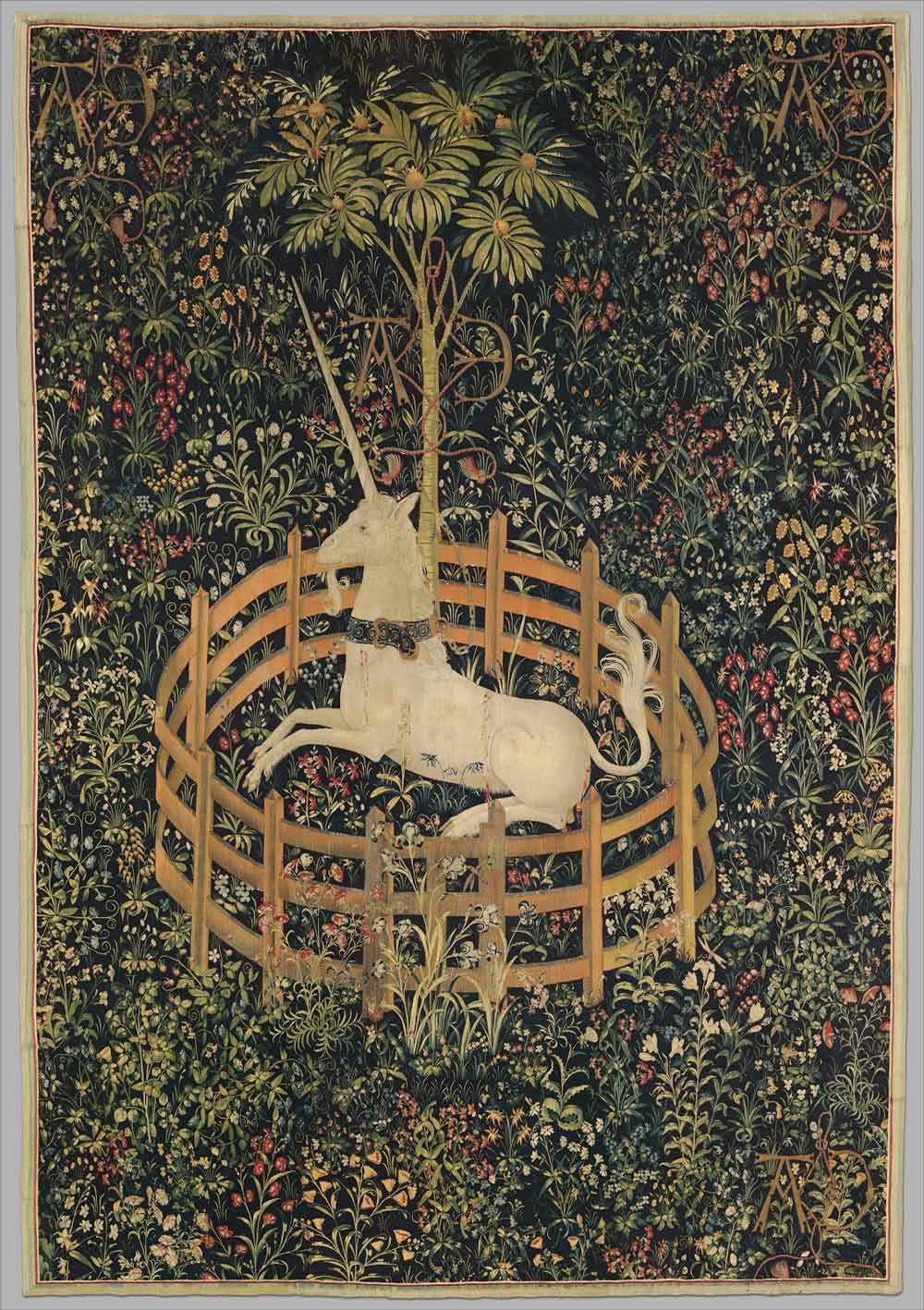

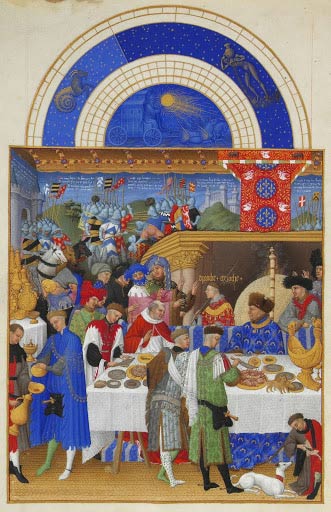

Earle turned to pre-Renaissance and medieval art for inspiration, not just from Europe but from Persia and the Middle East. He was drawn to a series of Persian gothic miniature paintings, whose flat, geometric style kept everything within the image in full focus. Another source would be Très Riches Heures du Duc de Berry (The Very Rich Hours of the Duke of Berry), a beautifully illustrated prayer book from 1410.

For 'Sleeping Beauty', Earle proposed a complete synthesis between character and environment, so that rather than there being two opposing styles (the background artwork and the animation, the former serving the latter), they would exist in harmony with one another. He also moved away from the principles in background art developed by Tyrus Wong and Claude Coats, and demanded that every element of the image be in focus at the same time, just as in medieval art.

Almost instantly, the animators expressed reservations. The artworks being created by Earle were bursting with intricate detail and geometric lines. They were worried that the characters would disappear into the backgrounds, especially if the same principles were applied to the animation itself, and that the sharp geometric style that Earle was insisting upon wouldn’t be as appealing to the audience as the more-rounded classic Disney style.

The characters became really unfortunately quite stiff. In order to fit this mannered background, they too took on a sort of cylindrical, geometrical shape that didn't lend itself to the, you might say, the ‘Bambi’ type of animation. It wasn’t really possible to make the characters fit the style and still be quite as attractive.

At first, many of the artists were excited by the challenges and ideas proposed in Earle’s stylings, but that excitement was short-lived. Over the next few years, they would be forced to forego their individual idiosyncrasies, and the principles of animation that had guided them for the last twenty years, in subservience to Earle’s vision. They were worried the film would be too cold, too overwhelming, without any heart or charm. When they brought this concern to Walt though, he backed Eyvind Earle. This was the approach he wanted to take, a serious and holistic one without the usual Disney gags. Even so, Walt had also become disconnected from the project, distracted by the demands of television and Disneyland. There wasn’t even solace to be found from the directing team - Eric Larson stuck to Walt’s demands and backed Earle.

The film was originally slated for Christmas 1955, but was soon delayed until 1957. As work progressed, it became clear that the film couldn’t possibly make that date either. By January 1957, after already five years of work, only 2500 feet of film had been animated. There were still 3800 feet left to go.

Sleeping Beauty was out of control.

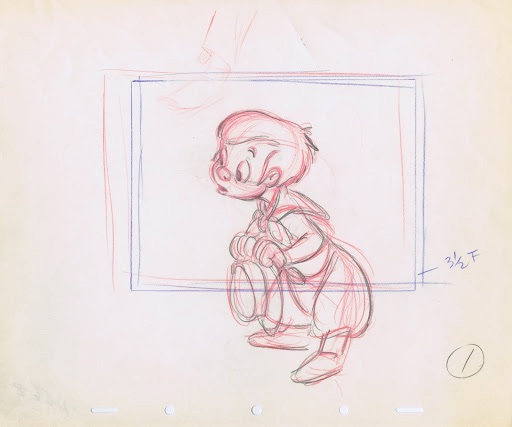

Eric Larson was born in Cleveland, Utah, on the 5th of September 1905, the son of Danish immigrants. After majoring in journalism from the University of Utah, Larson built a strong reputation as a humorist and cartoonist, and worked as a freelance artist. In 1933, after encouragement from a friend, he submitted his work to Walt Disney Productions and was hired as an assistant animator.

Larson joined Disney at the height of the Silly Symphony series, and within a few years, had been promoted to animator. During this time, he was mentored by some of the legendary Golden Age animators, in particular Hamilton Luske. He instilled in Larson strong principles of caricature, sincerity and action, all of which would become trademark qualities of Larson’s work.

With the move into features, Larson worked on every single one of the Golden Age films, animating Figaro in 'Pinocchio' and acting as supervising animator on the Pastoral Symphony in 'Fantasia' and on 'Bambi'. Much of his work during the films of the 30s and 40s focused on animal characters, imbuing them with a strong sense of humour, personality and empathy (and anarchy, in the case of the Aracuan in 'The Three Caballeros'), but by the Silver Age, Larson had become an expert at female characters, co-supervising 'Cinderella' with Marc Davis, as well as Alice, Wendy and Lady. When Walt appointed him one of the sequence directors on 'Sleeping Beauty', it was an acknowledgment to this particular skill and his strong attention to detail, necessary to achieving the demands of Eyvind Earle.

Perhaps Larson’s greatest contribution to Disney animation though, on par with his incredible draftsmanship and artistry, was his mentorship of the artists that would follow the Nine Old Men. In 1973, with the studio struggling to find its footing after the death of Walt, Larson established a training program to bring fresh artists to Disney. Many of those who were part of the program, including Ron Clements, John Musker, Glen Keane, Don Bluth, Andreas Deja, John Lasseter, Brad Bird and Tim Burton, would be among the most important animators and filmmakers at the end of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first.

Our only limit in animation is our own imaginations, and our ability to draw what we imagine.

Larson retired in 1986, having finished his time at Disney as animation consultant on 'The Fox and the Hound', 'The Black Cauldron' and 'The Great Mouse Detective', the first film directed by his students Musker and Clements. By the time he left the studio, he was the longest-standing employee in the studio’s history, having contributed to films, shorts and television at Disney for over 50 years. Speaking of Larson, Musker wrote how he “found the essential truth, warmth and sincerity of whatever character he animated”. When he passed away in October 1988 at the age of 83, he left behind a legacy not only found in the pencil lines of many of the great Disney animated films of the past, but the pencil lines and pixels of the great films to come.

'I want a moving illustration,' [Walt] said. I felt his sincerity. To me his words summed it all up: to Walt nothing was impossible...

The animation staff rallied against the geometric principles being imposed by Earle and character designer Tom Oreb. The original designs for Aurora resembled the figure and shape of Audrey Hepburn, but Earle redesigned her to be, according to animator Ron Dias, “very angular, moving with more fluidity and elegance, but her design had a harder line. The edges of her dress became squarer, pointed even, and the back of her head came almost to a point rather than round and cuddly like the other Disney girls. It had to be done to complement the background."

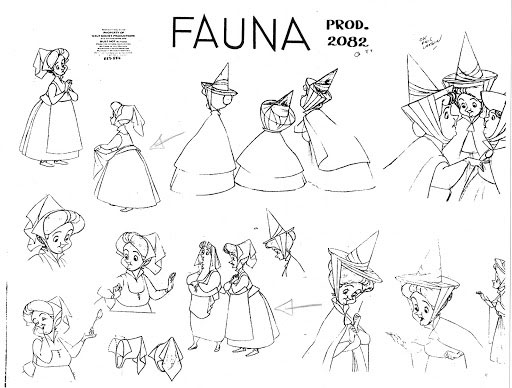

Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnson had already fought one battle with the design of the Three Good Fairies, after Walt had suggested they all look and behave the same and the two animators had argued to give them all distinctive personalities. Now they pushed back against the geometry of Oreb’s designs, worried that such a sharp look would make them unsympathetic. In the end, they came to a compromise, melding the two principles together, and in the process making Flora, Fauna and Merryweather the characters closest to the classic Disney style.

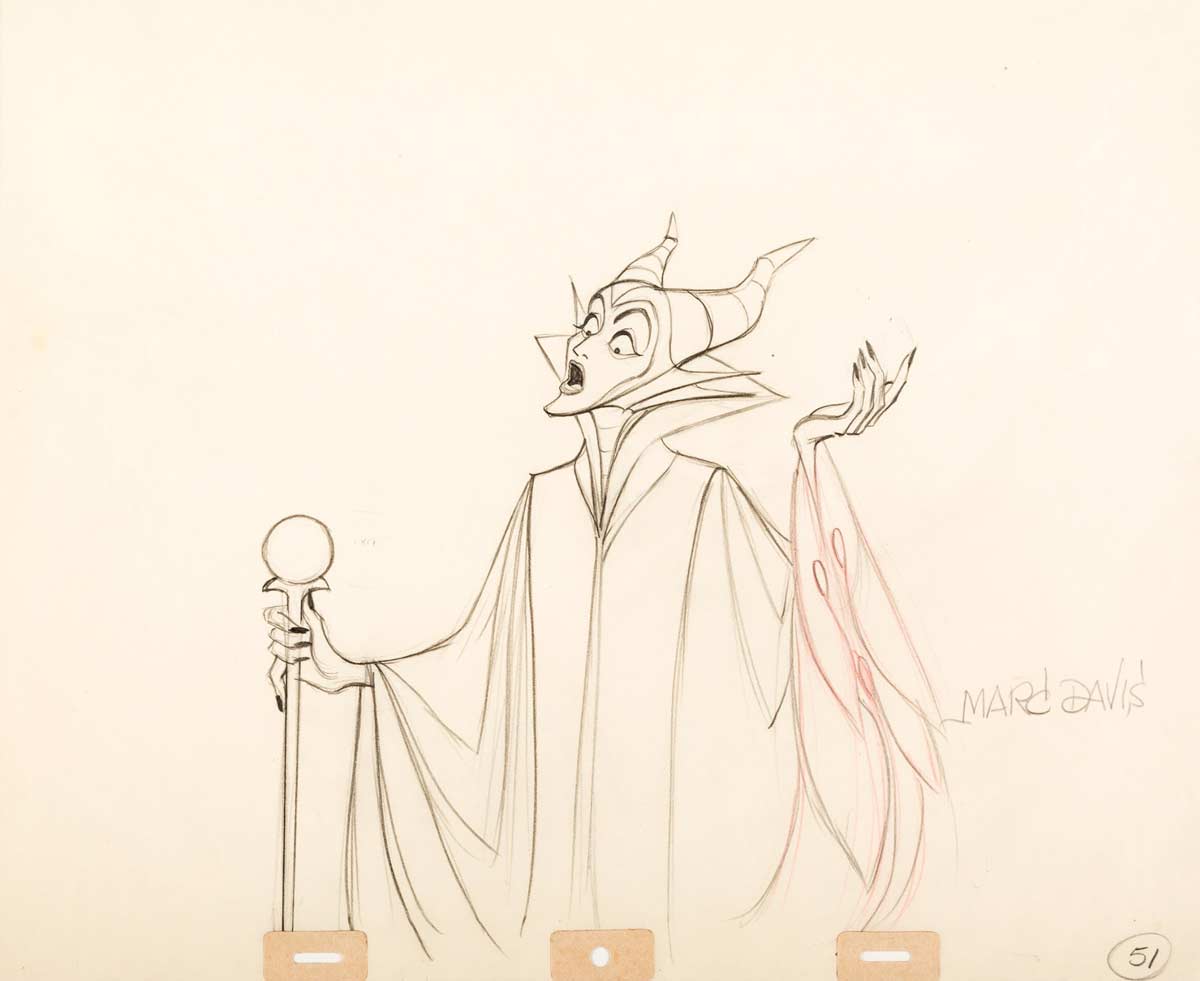

One animator who did get along well with Earle was Marc Davis. The two men bonded over their shared love of modern art, and Davis was willing to adhere to Earle’s principles when realising Maleficent. He was inspired by Czechoslovakian religious paintings, and with her black-and-lavender colouring and striking horned silhouette, created the most powerful and dramatic of all the Disney villains. His one concern was the fact that Maleficent tended to mostly deliver soliloquies with no other characters to bounce off from, so he added the Raven as her companion.

As production continued to slouch forward, with no end in sight and Walt essentially disconnected from the project, the tension and stress began to take a toll. Frank Thomas would complain to animation supervisor Ken Peterson, but was told that, because of Walt’s demands, nothing could be done. During production, Thomas developed a strange red sore on his face that refused to heal, and needed to visit the doctor every week to have it seen to. Many of the clean-up animators were so paranoid about getting anything wrong that they were only producing one drawing a day, equating to one second of usable footage a month.

They measured the width of a line, the density of the line, the taper of the line. ‘Cause we thought we were making the Lord’s Prayer, for sure.

When Walt finally did turn his attention back to 'Sleeping Beauty', he was horrified. He accused the artists of being too obsessed with detail rather than character, a similar complaint he had had on previous films, but this time they had been acting under his instructions.

His greatest concern though was with Sequence 8, which covered Aurora and Phillip’s meeting in the woods and was being directed by Eric Larson. Walt had seen an early version of the sequence and had found it cold and dull, suggesting they add some animals to lighten the mood. It was now a year later though, and not only had the sequence not been completed, thanks to Larson’s insistence on perfection, but had completely blown its budget, costing over $10,000.

Walt had no choice but to remove Larson as supervising director on 'Sleeping Beauty', and redeploy him as an animator on other projects. Clyde Geronimi now stepped in as supervising director, with Wolfgang Reitherman and Les Clark brought on as sequence directors. Geronimi instantly began to clash with Eyvind Earle over creative differences. In his interview with Michael Barrier and Milton Grey in 2015, Geronimi said that Earle’s artwork "lacked the mood in a lot of things. All that beautiful detail in the trees, the bark, and all that, that's all well and good, but who the hell's going to look at that? The backgrounds became more important than the animation. He'd made them more like Christmas cards."

Sleeping Beauty missed its February 1937 release date, and then its Christmas 1937 release date. It was already the longest-running production in the studio’s history, and shaping up to be their most expensive. As well as Earle’s artistic demands and the overall pedantic attention to detail, another hurdle was the decision to use the Super Technorama 70mm format, the first film of any kind ever to do so. The format was even wider than the CinemaScope format used on Lady and the Tramp, and the 70mm negative captured an alarming amount of detail. “When you have three fairies,” said Ollie Johnson, “and you want a close-up of a fairy, it’s impossible unless you’re going to get it to just the eyes or something. You couldn’t get rid of a fairy. I mean, you’d end up with three of them, there was no way around it. And that took a long time because you’ve got to draw all that stuff so carefully.”

Many of the artists also blamed Walt’s absence for the drawn-out process. While the story had mostly been settled on since 1953, there was still much detail to work out, and the general consensus was that the cold, austere nature of the film could have been prevented with Walt’s participation, or at least guidance. “He wouldn't have story meetings,” recalled Milt Kahl. “He wouldn't get the damn thing moving.”

In March 1958, with 'Sleeping Beauty' having missed two more release dates, Eyvind Earle left the project to work for John Sutherland Productions. It isn’t clear whether his decision to leave Disney had anything to do with tensions on the film, but it would be almost another year before it would reach the screen. As soon as Earle left, Geromini had the textures in his backgrounds softened and diluted, but Earle had achieved something monumental with his work on 'Sleeping Beauty'. Walt had wanted him to push the film to its visual limits, and Earle had exceeded all expectations. No animated film of this scale had been made before, and no animated film of this scale would ever be made again.

A new release date was set for January 1959, and this one had to be adhered to. Walt may have said that time and money didn’t matter for this magnum opus, but now Sleeping Beauty had become so enormous that it was devouring the studio’s resources. It needed to come to an end.

In a famous photograph from the making of 'Sleeping Beauty', Walt and Eric Larson are standing in a corridor, looking at the artwork from the film that covers the walls. Many years later, animator Andreas Deja asked Larson what he and Walt had been discussing, whether they had been looking at the artwork and taking in what they had achieved. No, he’d replied. It wasn’t a congratulatory conversation. Walt was telling Larson that Sleeping Beauty was now costing so much money that, if it failed at the box office, Walt Disney Productions might never be able to make another animated feature film again.

- Wikipedia on Sleeping Beauty, the original fairy tale, Eyvind Earle, Eric Larson, George Bruns, Floyd Norman, Super Technorama 70, and the Unicorn Tapestries.

- Sleeping Beauty: Platinum Edition, Blu-ray, 2009

- Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, Neal Gabler, 2006

- Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, Mindy Johnson, 2017

- The Disney Studio Story, Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, 1988

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume II - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Musical Years (The 1940’s - Part I), Didier Ghez, 2015

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume IV - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Period (The 1950’s and 1960’s), Didier Ghez, 2016

- Sleeping Beauty: The Legacy Collection, soundtrack release notes, Paula Sigman-Lowery, Russell Schroeder and Randy Thornton, Walt Disney Records, 2014

- Interview with Gerry Geronimo, Michael Barrier and Milton Grey, 2015

- The 100 Most Influential Sequences in Animation History, Edited by Eric Vilas-Boas and John Maher, Vulture, October 5 2020

- Walt Disney’s 'Sleeping Beauty' Sound Track on Records, Greg Ehrbar Cartoon Research, April 2, 2018