Music ∷ Sam Porter

Show Artwork ∷ Nikolaos Pirounakis

Episode Artwork ∷ Lily Meek

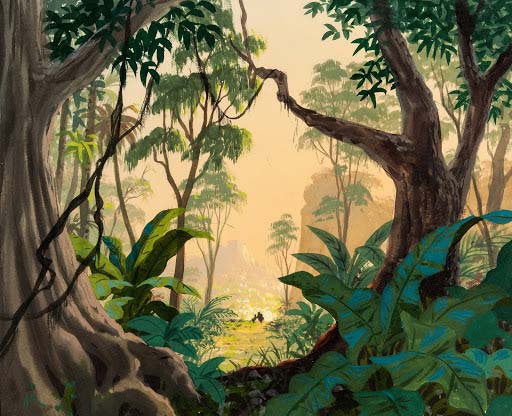

In the meantime, work continued on the next Disney animated feature, one that, despite the collective enthusiasm for it, was proving a frustrating challenge. After years of neglect, Walt was unusually active in its development, pushing the artists away from the tendencies he saw as ulterior to what he had begun in the late 1930s. The film would be a dazzling, riotous and surprisingly haunting piece of entertainment, one whose simple parameters gave room for all involved to deliver some of the best work of their careers. Unbeknownst to everyone though, this film would also be the end of an era, a flash of joy and energy before the unimaginable would occur. Just as a little boy named Mowgli would be led to a life without his parental figures to protect him, so Walt Disney was unknowingly preparing his animation staff for a life without him.

Man, that's what I call a swinging party.

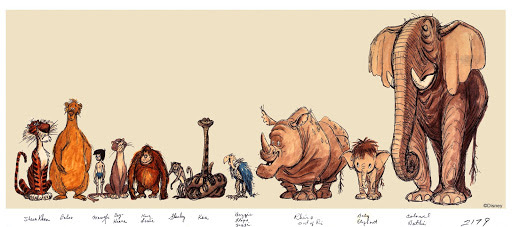

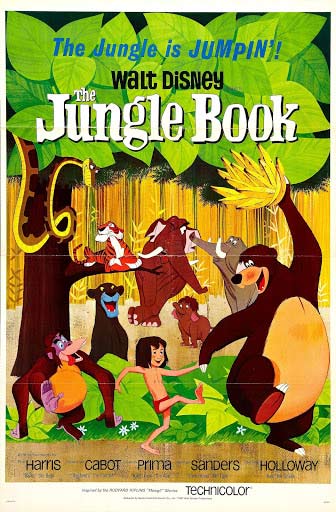

In the forests of India, a panther named Bagheera (Sebastian Cabot) finds a baby boy alone in a wrecked boat. Knowing the baby will die, he takes him to a pack of wolves who have recently had a litter. The wolves adopt him and name him Mowgli. Many years later, news of the return of the man-eating tiger Shere Khan (George Sanders) puts the life of Mowgli (Bruce Reitherman) in danger. Bagheera decides to take him to a nearby Man Village, something Mowgli does not want to do, especially when he meets the laid-back bear Baloo (Phil Harris). Baloo wants to adopt Mowgli, but Bagheera convinces him that the Man Village is the best place for him. Devastated at this betrayal, Mowgli runs away, and after a narrow escape from the clutches of the python Kaa (Sterling Holloway), he ends up in the path of Shere Khan. Baloo and Bagheera arrive just in time, and Baloo fights the tiger, but using fire from a recent thunder strike, Mowgli scares Shere Khan away. Just as they are preparing to return to the jungle, Mowgli sees a young girl collecting water at the river. Fascinated, he follows her to the Man Village, and satisfied that Mowgli is now safe, Baloo and Bagheera return to the jungle.

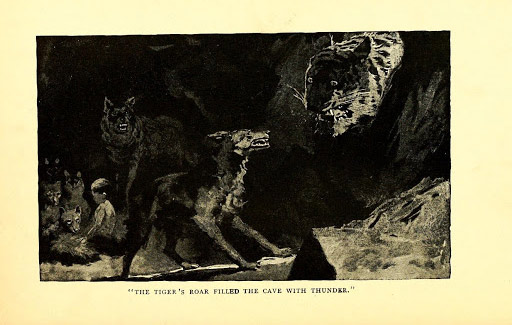

With 'The Jungle Book', Walt Disney Productions once again would tackle a literary giant, the most famous work by legendary British journalist and writer Joseph Rudyard Kipling. Kipling was born in Bombay, India in 1865, moving with his family to the United Kingdom when he was five before returning as an adult. For this reason, India features heavily in much of his writing, including the short stories that make up 'The Jungle Book', published in 1894, and its sequel, ‘The Second Jungle Book’, in 1895.

Kipling likely began conceiving of the stories for his daughter Josephine, who died only a few years after the second volume was published at the age of six. He drew upon ancient Indian storytelling fables, such as those told in the ‘Panchatantra’ and the ‘Jataka tales’. The stories were originally published in magazines in 1893 and 1894, and written by Kipling while he was living in Vermont in the United States. While they also include stories with featuring other characters, such as a fearless mongoose and an intrepid white seal, the most beloved are those concerning Mowgli, a boy raised by wolves in the jungles of India, his adventures moving between a life in the jungle and in the human world, and the animals who teach him the Laws of the Jungle that allow him to survive.

Both volumes of 'The Jungle Book' were met with instant acclaim, and together have become an enduring classic, not just in children’s literature as they were intended by Kipling, but western literature in general, despite criticisms of its commentary on race and imperialism. The stories have been adapted into many different mediums since publication, with film adaptations appearing from the 1930s. For the most part, these adaptations have focused on the Mowgli stories, including a lavish Technicolor production in 1942 directed by Zoltan Korda and starring Sabu.

It was this adaptation that was fresh in everyone’s minds when Bill Peet suggested 'The Jungle Book' as a follow-up project to 'The Sword in the Stone'. He suggested that the animation department could do more interesting animal characters, perhaps to appease those that had been strong supporters of the abandoned ‘Chanticleer’ project, and Walt found the idea appealing. The film rights were purchased and Peet began work on the adaptation, adopting the same method he had used on ‘Dalmatians’ and 'The Sword in the Stone' of tackling the screenplay before the storyboards.

As had been the case with ‘Alice in Wonderland’ though, the shadow of the source material proved a difficult one to shake. The joyous film we see today went through many years of difficult development and debate, not just on how to approach Kipling’s masterpiece, but how to approach storytelling in animation in general. After over a decade of neglect, Walt Disney would once again put his singular story skills to the task, and in his mind, return the Disney animated feature to the principles which had established the form in the first place. 'The Jungle Book' would be a decisive moment in the history of Disney animation, a turning point for what had been and what was to come.

While Peet was working on 'The Jungle Book', Walt began to look at what had been done on 'The Sword in the Stone', and was unhappy with what he saw. His faith in Bill Peet was beginning to wane, and he decided that he needed to be more involved with development on their next film. Peet submitted a treatment in April 1963, and Walt outright rejected it. He thought it was too dark and too serious for a family-friendly film, and was far too reverent to the tone of Kipling’s stories. He asked Peet to give it another go, but Peet wasn’t interested in taking the film in the direction Walt wanted. They were adapting Kipling’s 'The Jungle Book', and that’s just what he intended to do.

Peet’s determination was causing friction between him and the rest of the team. He had been the most respected story man at Disney for many years now, and he was overly confident in his abilities. In a memo to Peet in January 1964, Wolfgang Reitherman (who was directing the film) warned Peet that he needed to recognise “the contribution the animators and the Music Room make to your story and their right to have a voice in these decisions”, here meaning voice and character. “Remember you are not going to animate the picture. That is our problem and a tough one too... It might be well to reflect that a cartoon feature represents two years of arduous effort on everyone’s part and we’ll never put a “fun” picture on the screen if we don’t all have “fun” and enthusiasm while making it.” This was Reitherman’s amiable conflict resolution skills in action, but on this occasion, they didn’t work.

Peet continued to work on 'The Jungle Book' throughout 1964, but Walt continued to reject his ideas, demanding the picture deviate further from Kipling. Finally, frustrated at the constant conflict, Bill Peet resigned from Walt Disney Productions on November 18, 1964, taking with him photostats of his completed storyboards. He had always intended to leave Disney after the film was completed to pursue a career writing and illustrating children’s books, but with progress on the film now at a halt, he saw no need in sticking around. Once Disney’s greatest story man, Bill Peet never returned to the studio again.

With Peet gone, Walt now needed to get 'The Jungle Book' back into shape, and this meant bringing in new blood. He called a meeting with Reitherman, writer Larry Clements, the Sherman Brothers and other key creatives. He asked if anyone in the room had actually read Kipling’s 'The Jungle Book'. No-one raised their hand. “Good,” he replied. “No one read it.” And then, just as he had done in the 1930s in the auditorium at Hyperion Studios with ‘Snow White’, Walt performed for them the story he wanted to tell, a simplified version of Peet’s narrative of Mowgli being taken to the Man Village by Baloo and Bagheera, but with a much more irreverent tone. Larry Clements was put in charge of writing the film, and the Shermans would write new songs, with all of Terry Gilkyson’s songs rejected - except one. Walt quite liked a song Terry had written called ‘The Bare Necessities’, and told the Shermans to keep it in the film.

This essentially brought 'The Jungle Book' back to square one, though many elements and character designs from Peet’s treatment would be carried over. They began to find their way reconstructing the film from the remains of Peet’s work and with Walt’s new story as a spine. “We’d start with the main sequence in the middle of the picture, not the beginning”, remembered Clements, “where all the main characters are in it. We’d learn our characters, and then from there, we’d expand either way.”

Deciding on this new tone though was difficult. The story was in constant flux, and many of the artists were having trouble finding something to hold on to. “[Walt] wanted to get in closer on the characters,” remembered story man Vance Gerry, “the story, the plot was of secondary importance to him. ‘Jungle Book’ was very difficult for me to work on. I just never knew where I was or what was going on.”

And then, Walt hit upon an idea that would completely change the course of the film. They had been struggling to find the right voice actor for Baloo the Bear, and consequently settle on what kind of character he would be. In Kipling’s story, Baloo is a wise, serious and bumbling figure, but Walt wanted him more gregarious. On a recent trip to Palm Springs, Walt had seen popular singer and actor Phil Harris performing, and thought he would be a good fit for the character. Many of the animators thought it was a terrible idea. “We went through a lot of bears before we got Phil,” recalled Reitherman, “and none of them seemed to be right. And finally, Walt says, ‘Why don’t we try Phil Harris?’, and of course, some of the animators said, ‘Phil Harris, in a Kipling film?’, and Walt says, ‘Why not? We’re going to make our own ‘Jungle Book’, we’ll do it our way.’”

Harris was brought in to test for the part, and to everyone’s surprise (including Harris), it was a perfect fit. Phil Harris’ easy showmanship finally cemented the character of Baloo, and in the process, the entire tone of the film. “We were trying to keep the flavour of Kipling,” recalled Milt Kahl, “but when Phil Harris came in, Kipling went out the window - and Walt just loved it.” Harris’ casting would influence the rhythm and comedy of the storytelling, the free-wheeling quality of the animation and the insatiable swing sound of both the Shermans’ songs and George Bruns’ score. It also gave the film its much-needed emotional centre. “The bear, who had been intended as a minor figure,” wrote Walt biographer Neal Gabler, “became the film’s co-star, converting the picture from a series of disconnected adventures into a story of a boy and his hedonistic mentor - a jungle Hal and Falstaff.”

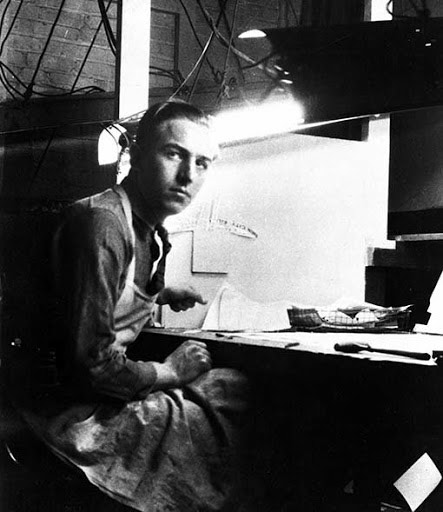

Oliver Martin Johnston Jr, the only son and youngest child of Oliver and Florence Johnston, was born on the 31st of October 1912 in Paolo Alto, California. After graduating from Paolo Alto High School, he attended Stanford University as an arts major, where his father was a professor of Romance languages. While at Stanford, Johnston worked on the campus humour magazine Stanford Chaparral, and it was here that he met lifelong friend and future collaborator Frank Thomas. In his senior year, Johnston transferred to the Chouinard Art Institute, and in 1935, was approached by Walt Disney Productions to join the staff.

Johnston began work as an in-betweener, before being promoted to apprentice animator under Fred Moore. He continued as an assistant on ‘Snow White’, but was promoted to animator on ‘Pinocchio’, where he worked on the title character. Around this time, he was also chosen as one of the four supervising animators on ‘Bambi’, an assignment on which he would work for many years. His most memorable work on ‘Bambi’ was with the character of Thumper, one of the most rambunctious and adorable characters in the Disney canon. With Thumper, Johnston built on the incredible skill he had demonstrated with personality and character in ‘Pinocchio’, delivering work full of wit, imagination and humanity.

The key to these characters is making them think, and making the expressions on their faces that register what they’re thinking, what they’re feelings are, what’s going on in their mind, and I think that’s the key to Disney animation, what Walt always asked for.

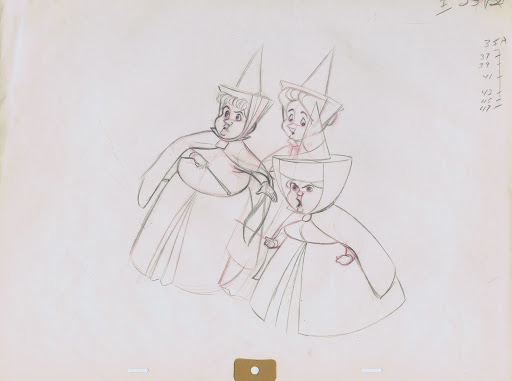

Throughout the war, Johnston continued to work as an animator, but with ‘Song of the South’, he was finally promoted to directing animator, a position he would hold on the next thirteen animated feature films. His work over those following thirty years would include some of the greatest Disney characters, including the King of Hearts, Lady, the Three Good Fairies, Pongo and Perdita, Archimedes and many of the cast of the Winnie-the-Pooh shorts. On ‘Peter Pan’, he was paired with Frank Thomas for the first time, and the two created comedy gold with the relationship between Thomas’ pompous Captain Hook and Johnston’s bumbling, brilliant Mr Smee. The two would continue to collaborate on films for the rest of their career at Disney, with 'The Jungle Book' representing the apex of that collaboration. For everyone at Disney, Frank and Ollie were seen as a pair, attached at the hip. Animator Glen Keane remembered that the two men would have lunch together each day, ruminating over each others’ sequences, discussing how they could be improved and how they could convince director Wolfang Reitherman to agree with them.

It was at the studio that Johnston met his wife, marrying ink and paint artist Marie Worthey in 1943. Johnston also had an intense love of trains, with one of his pet projects being to build and collect working scale models. He shared this love with fellow animator Ward Kimball, and was partly responsible for fuelling Walt’s love for trains as well.

Johnston’s guiding principle as an animator was not to worry about what the character was doing, but what they were thinking, and let their inner psychology guide their movement and behaviour. The manner in which Johnston’s characters behave is often subtle and instinctual, small human movements that would usually be overlooked but are necessary in giving them a believable inner life. One example often cited is the moment between Pongo and Perdita under the stove. With limited space, Johnston tapped into the relationship between the two dogs, what it was that Perdita needed in that moment, and how Pongo could best comfort her with so few ways to do so. The deceptive simplicity of Johnston’s work is easy to miss, but when noticed, takes your breath away.

The final film on which Johnston would work would be ‘The Fox and the Hound’, but despite retiring from Disney in 1978, he would continue to have a strong relationship with the company, becoming one of the biggest advocates for Disney animation in its failing years. He and Thomas would become the public face of the art form, culminating in their authoritative book ‘Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life’, which outlined the twelve principles of animation while offering a thorough technical history of animation at Disney. Published in 1981, the book is now one of the major reference books on animation, and the two men would write a further three books together, including a book on the making of Bambi. Johnston also mentored many of the next generation of animators at Disney, including Brad Bird, who would include cameos for Johnston in ‘The Iron Giant’ (1999) and ‘The Incredibles’ (2004).

With the death of Frank Thomas in 2004, Ollie Johnston became the last surviving member of the Nine Old Men. As Disney animation was entering the uncertainty of the new century and computer-driven animation, he became the last surviving link to the early days of the art form, a role he took very seriously as he continued to represent the films he had worked on and his colleagues who were no longer there. In November 2005, Johnston received the National Medal of the Arts from President George W. Bush in a ceremony at the White House.

On the 14th of April 2008, Ollie Johnston passed away of natural causes, bringing his remarkable career and the story of the Nine Old Men to a close. In many ways, it was fitting that Johnston would carry that legacy the longest. His belief in the power of animation is there in every single pencil stroke, in every burst of imagination, in every beautifully realised, startlingly complete character.

What happened was that the characters started to become rich, and Walt devised a story there. He had an awful lot to do with the richness of the characters to start with.

Bolstered by the casting of Harris, Walt aimed just as high for the rest of the cast. While Sebastian Cabot, who would voice Bagheera the panther, had already featured in 'The Sword in the Stone' as Sir Ector, he was a popular actor on television, and Sterling Holloway, a Disney voice veteren, had delivered an iconic performance as Winnie-the-Pooh in ‘Winnie-the-Pooh and the Honey Tree’, though his performance as Kaa the Snake was far from that warm, cuddly character. After Harris was cast, Disneyland Records Jimmy Johnson suggested Walt approach popular American singer Louis Prima to voice King Louie the Orangutan, a perfect foil to Harris’ Baloo. There was even a suggestion that the vultures could be voiced by The Beatles, though John Lennon objected to the band starring in an animated film. The most high profile casting decision would be Oscar-winning actor George Sanders as Shere Khan.

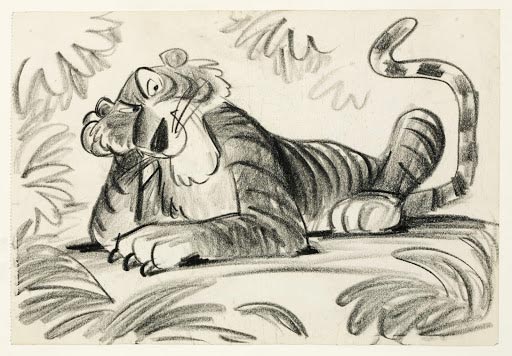

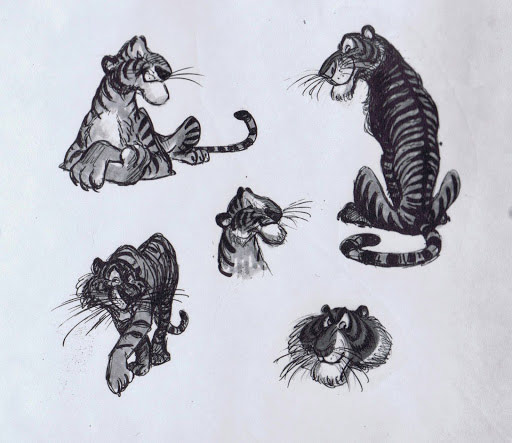

The casting would also influence the design of the characters themselves. The animators had often fed off the personalities of the voice cast for how the characters should look and move, but with 'The Jungle Book', caricatures of the actors themselves crept in. “In 'The Jungle Book' we tried to incorporate the personalities of the actors that do the voices into the cartoon characters,” said Wolfgang Reitherman, “and we came up with something totally different. When Phil Harris did the voice of Baloo, he gave it a bubble of life. We didn't coach him, just let it happen." The clearest example is Shere Khan, where Ken Anderson drew on George Sanders’ distinctive look. “When we started the picture, we were thinking about a more two-dimensional villain,” remembered Milt Kahl. “Then Ken Anderson did a drawing of a tiger with Basil Rathbone in mind - a supercilious character, who was kind of above it all. He became quite a powerful character - so polite and understated.” The marriage of Sanders’ sublime vocal performance, Anderson’s delicious design and Kahl’s extraordinary animation would make Shere Khan one of the most dangerous and menacing Disney villains.

The casting would also influence how the Sherman Brothers and George Bruns would approach the sound of 'The Jungle Book'. The presence of Harris and Prima meant that the score could embrace more of a jazz-infused sound, especially with Harris and Prima’s show-stopping duet ‘I Wanna Be Like You’. The two men weren’t able to record together, so Prima and his band recorded their side first. The scatting between Louie and Baloo was pre-written with Baloo simply repeating Louie, but when Harris came to record it, he found it too difficult. Reitherman gave him permission to do whatever he wanted, and Harris’ improvised his own responses. His work is so spontaneous that you’d swear the two men must have recorded together.

Walt had very specific instructions for the Sherman Brothers. The music needed to make the film as fun as possible. He told them to find all the scary places in the story, and to make sure there was a lively, fun song in its place. He also wanted the songs to advance the story rather than comment on it, so that the action kept moving. It was a simple request, but almost no Disney animated film had employed music in this way before. After their tempestuous experience on 'The Sword in the Stone', George Bruns and the Shermans were more attuned to one another, and as well as being one of Brun’s best scores, a haunting and mysterious work that recalls the tone of Kipling’s stories, the Sherman Brothers’ songs were now more fully integrated, especially the final song ‘My Own Home’, which they regarded as the theme for the film.

For the part of Mowgli, another young voice actor had been cast, but just as had happened with 'The Sword in the Stone', his voice began to break before recording was completed. Once again, Wolfgang Reitherman turned to one of his three sons to replace the actor, but rather than cobble the two performances together as he had done with 'The Sword in the Stone', Bruce Reitherman would re-record the entire performance as Mowgli. Having just directed Bruce as the voice of Christopher Robin in ‘Winnie-the-Pooh and the Honey Tree’, Reitherman knew how to elicit a great performance from his son. As well as providing the voice of Mowgli, reference footage of Bruce was shot, some of which would be reused in later Winnie-the-Pooh shorts.

The animation process on 'The Jungle Book' began on May 22, 1966, and the episodic structure of the narrative meant that the animators were focusing on self-contained sequences. Reitherman was now far more confident in his role as director, and that confidence was reflected in his relationship with the animation team. “On ‘Jungle Book’,” remembered Ollie Johnson, “Wollie Reitherman... let us who were more experienced take sequences, so you had a lot to say about how your sequence would be cut and the way it would be developed, the way the material would be handled and the way you saw the characters personally, and they way they would relate to each other. So it was a great creative experience.”

I think it’s awfully important to give a great deal of creative credit to the animators. It isn’t easy giving animals a human personality.

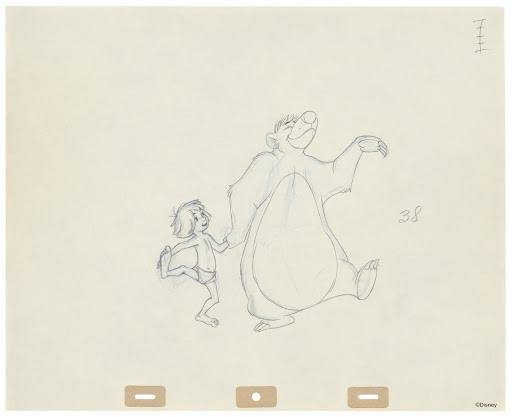

In the end, Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnson would animate almost half of the film, in particular the scenes between Baloo and Mowgli. The two primary scenes between the characters are a perfect demonstration of the full range of their abilities - ‘The Bare Necessities’ sequence is a masterpiece of character animation, as lively and spontaneous as Terry Gilkyson’s song, while the scene where Baloo tells Mowgli he has to go to the Man Village is full of subtle, powerful details that are still studied by animators today. John Lounsbery would also put his skill with animals to incredible use with Colonel Hathi’s elephants, as well as delivering one of his greatest feats with the dance sequence in ‘I Wanna Be Like You’.

The look, sound and feel of 'The Jungle Book' had been solved, but even though production was in full swing, the story was still being worked out. Walt was being pedantic in how the story should be approached, with the characters and their motivations driving the narrative. As the characters became more appealing though, and the relationship between Mowgli and Baloo became the heart of the film, a serious problem began to emerge - how on earth were they going to end it? It was clear that the story needed to end with Mowgli deciding to live in the Man Village, but the jungle now seemed the more appealing option. “Walt wanted Mowgli to make the decision himself to go to the Man Village,” remembered Ollie Johnston, “he didn’t want anyone forcing the boy.”

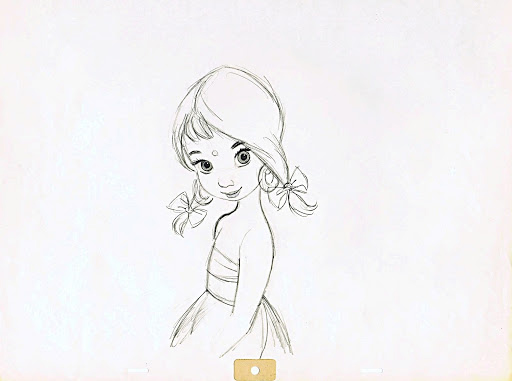

To find an answer, Walt broke his own rule and turned to Kipling. Throughout the stories, he makes reference to Mowgli eventually leaving the jungle and starting a family, and Walt thought that this could be the key to convincing him to stay. He proposed a sequence where Mowgli sees a young girl collecting water from the river and, fascinated by her, follows her back to the village. The animators and story team thought it was a terrible idea, but Walt insisted on giving it a try. The Shermans were sent away to write a song, and Ken Anderson to storyboard the sequence. Working independently of one another, they were surprised to find that Anderson’s sequence and the Shermans’ song ‘My Own Home’ fitted together perfectly.

Walt assigned the sequence to Ollie Johnston, who was still sceptical the idea would work. As he began though, he warmed to the idea, and delivered one of the most haunting moments of the film. The sequence is an astonishing marriage of talents - the Shermans’ beguiling song, the mysterious orchestrations by Walter Sheets, and Johnston’s astute, delicate animation. We watch as Mowgli slips from childhood to adulthood, the motivation they needed for him to leave the jungle.

Sometimes a storyline that’s too complicated can get in the way, and ‘The Jungle Book’ had the simplest storyline ever. The storyline didn’t get in the way of the characters, that’s the beauty of that little picture.

The making of 'The Jungle Book' was a fruitful and creative period for everyone involved. On the one hand, they were elevating the Xerox-era animation to new heights, feeding off the artistic energy from every department of the production. On the other, Walt was returning them to the essential storytelling principles that had guided their legendary early films, and away from the confusion that had plagued their recent efforts. Without realising, he was preparing his artists for making films on their own. “Walt could put his finger in the total theme of a picture and story so quickly”, remembered Wolfgang Reitherman. “All the way through ‘Jungle Book’, I tried to go for personalities and not get a complicated story. In the pictures I’ve made since then, I’ve gone for personality, strong characterisations, strong voices that fit the characters. It made the pictures ever so much simpler to construct.”

‘The Jungle Book’ was the most involved Walt had been in the making of a Disney animated feature in many, many years, and his fingerprints can be seen all over it. Just under a year before release though, his energy began to wane. After watching rushes from the film, he sighed and turned to the animators. “I don’t know, fellows”, he said. “I guess I’m getting too old for animation.”

He would not see the film completed.

It was in Kansas City that Walt and Ub Iwerks began to develop their skills as animators. They created the first Laugh-O-Grams there, and when those didn’t bring in enough income to keep the company going, the first of the ‘Alice’s Wonderland’ shorts. In 1923, with that film finished and no distributor, Walt followed Roy to Hollywood, and together they formed the Disney Brothers Studio, a company they would run together for the next forty-three years. In 1925, they hired an artist named Lillian Bounds as an inker, and in July that year, Walt and Lillian were married. Together, they would have a daughter, Diane, and adopt another, Sharon.

By 1966, Walt Disney was one of the most powerful figures in the entertainment industry. His successes were legendary, from the creation of Mickey Mouse, to the first animated feature film ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’, to the iconic amusement park Disneyland. He had been hailed as a genius and a visionary, dismissed as a peddler of common entertainment, accused of bigotry, bullying and conservatism. His face, name and voice were known to millions of people all around the world. Under his guidance and insistence, his company had changed the face of cinema, television and entertainment, and amongst the gloss and the showmanship, delivered some of the greatest artistic achievements of the twentieth century.

On the 27th of October 1966, Walt sat down to film a special introduction to an invitational showing of their recent live-action film ‘Follow Me, Boys!’ He apologises for not being able to be there in person, caught up in the filming of their new comedy, ‘Bluebeard’s Ghost’. He then introduces their upcoming musical ‘The Happiest Millionaire’, featuring Greer Garson and Fred MacMurray, as well as “newcomer Lesley Ann Warren”. He looks older, his voice has an edge of exhaustion to it, but there’s still the perennial twinkle in his eye. After playing a clip from the film, he brings the subject back to ‘Follow Me, Boys!’, and makes special mention of “a fifteen-year-old boy for whom I predict a great acting future. His name is Kurt Russell.” As the camera pulls back, he tells the audience to make sure they have a handkerchief handy.

This would be the last appearance of Walt Disney ever captured on film. During 1966, he had noticed a shortness of breath and sudden weight loss, significant enough for staff at the studio to notice. On the 11th of November, he was admitted to UCLA Medical Centre for a procedure to relieve the pain in his neck and leg, connected to an injury he had sustained while playing polo in 1938. During the diagnostic workup prior to the procedure though, doctors found spots on his left lung. He was immediately transferred to St. Joseph’s Hospital for surgery, which just happened to be opposite the studio. The following day, Walt’s family gathered at the hospital to hear the results of the surgery. Walt had lung cancer. The doctors gave him six months to two years to live.

Walt had been a heavy smoker most of his life, preferencing unfiltered cigarettes. After decades of smoking, a malignant tumour had grown and had now metastasized. They immediately began cobalt treatments, but in the meantime, his diagnosis was kept a secret. An official press release announced that a lesion had been found on his left lung, causing an abscess that necessitated part of the lung being removed. On the 21st of November, he was discharged and returned to the studio. It was clear to everyone that something was wrong, Ward Kimball remembering, “He looked defeated for the first time.” Walt conducted himself as business as usual, watching a rough cut of ‘The Happiest Millionaire’ and continuing to discuss plans for EPCOT, his futuristic city attached to Disneyworld in Florida, but on November 30, he was rushed from his property in Palm Springs back to St Joseph’s Hospital, where his condition deteriorated quickly.

Walter Elias Disney passed away at 9.35am on the 15th of December 1966, ten days after his 65th birthday. The news reached the studio from across the street. Everyone was sent home for the day, but many stayed, shellshocked, unsure of what to do. Two days later, Walt’s remains were cremated and interred at Forest Lawn Memorial Park in Glendale, California.

On the 15th of December, the day after Walt’s death, Roy issued a statement to the employees of Walt Disney Productions. He wrote:

"The death of Walt Disney is a loss to all the people of the world. In everything he did Walt had an intuitive way of reaching out and touching the hearts and minds of young and old alike. His entertainment was an international language. For more than 40 years people have looked to Walt Disney for the finest in family entertainment.

"There is no way to replace Walt Disney. He was an extraordinary man. Perhaps there will never be another like him. I know that we who worked at his side for all these years will always cherish the years and the minutes we spent in helping Walt Disney entertain the people of the world. The world will always be a better place because Walt Disney was its master showman.”

‘The Jungle Book’ was released on the 18th of October 1967, ten months after Walt’s death. Wolfgang Reitherman led the team through the final stages of production. Despite Walt’s increased involvement in the project, the film had given the artists a strong sense of autonomy, bolstered by the knowledge that they had his confidence in the work they were doing. They needed that confidence to bring the production back together and to the finish line.

The critical response to 'The Jungle Book' was uniformly ecstatic, despite the fact that, as Time put it, “‘The Jungle Book’ is based on Kipling in the same way a fox hunt is based on foxes.” In the New York Times, Howard Thompson praised its “simple, uncluttered, straight-forward fun, as put together by the director, Wolfgang Reitherman, four screen writers and the usual small army of technicians. Using some lovely exotic pastel backgrounds and a nice clutch of tunes, the picture unfolds like an intelligent comic-strip fairy tale.” It was impossible though to view the film separate from the death of Walt Disney, and many critics tied their praise with a larger acknowledgement of his legacy. “The reasons for its success,” wrote Time, “lie in Disney’s own unfettered animal spirit, his ability to be childlike without being childish... It is the happiest possible way to remember Walt Disney.”

The film had cost $4 million to make, but on its initial box office run, the film made an impressive $11.5 million. By the time it left theatres the following year, its worldwide box office gross was $23.8 million, making it the most successful animated film released to that point. At the Academy Awards, the film was nominated for Best Song, not for any of the Sherman Brothers’ work, but for the only remaining song by Terry Gilkyson in the film - ‘The Bare Necessities’. Gregory Peck, then president of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences, also lobbied to have the film nominated for Best Picture, but this never came to be.

With each subsequent re-release, 'The Jungle Book' continued to break box office records and garner acclaim. It stands as the biggest box office hit in Germany’s history in terms of admissions with 27.3 million tickets sold, 10 million more than ‘Titanic’, and the third-highest in terms of box office earnings behind ‘Avatar’ and ‘Titanic’. Once introduced on home video, 'The Jungle Book' would prove to be one of the most successful home entertainment releases of all time across the globe. Some controversy has followed the film though, with concerns that King Louie relies on racist African American stereotypes, made all the more complicated by linking those stereotypes with an ape character. The film is one of those on Disney+ accompanied by a warning for negative depictions.

As an animator, it’s probably the greatest film in terms of character development and how characters play against one another.

For animators today, the film is one of the most revered, respected and studied of the Disney animated classics. Many regard the character animation as the finest captured on film, and go back to the original drawings in the Walt Disney Archives to study directly from them. During the 1990s and 2000s, the film became a reference point for many of the Disney films made in this period, and some of the most acclaimed animators of that generation, including Brad Bird, Andreas Deja, Glen Keane and Sergio Pablos, credit the film as the reason they became animators in the first place.

‘The Jungle Book’ is one of the most ecstatic, joyous and beautiful films in the Disney canon. It is one of those rare works that hardly puts a foot wrong, and while most films with such an episodic structure are often unsatisfying or unsuccessful, that very structure is part of its magic. Every sequence is a marvel, each building on the success of the last, and the insistence on a narrative driven by character rather than plot help tie them all together into an emotionally fulfilling whole. The characters are remarkably realised, the world is beguiling and dangerous and magical, and its central conceit - on the perils of growing up, the complex relationship between children and their caregivers, and how our actions speak to the person we are to become - still sing across the decades.

Most remarkable of all, with Mowgli, 'The Jungle Book' is the very first Disney animated film to feature a protagonist that is a person of colour. Though very little of the film speaks to Indian culture, the fact that a character with a skin other than white can be seen as a hero, not a stereotype, in a Disney film from the 1960s is remarkable, especially in how little attention the film pays to this fact. Mowgli would be the only person of colour to lead the ensemble in a Disney animated film until ‘Aladdin’ in 1992, 25 years later.

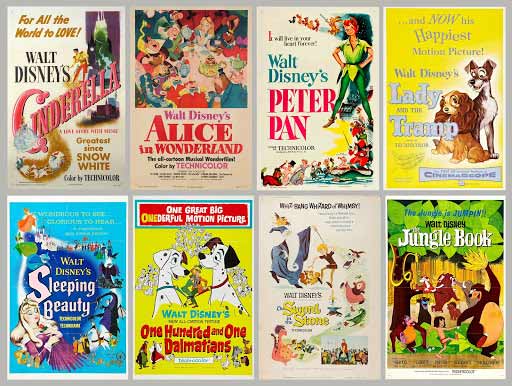

For the artists at Walt Disney Productions in 1967, the enormous success of 'The Jungle Book' must have been a bittersweet one. Walt was not there to celebrate with them, to see the fruits of their collective labours. When they looked at the film though, they could do so with pride. During the Silver Age, begun with uncertainty and blind faith with ‘Cinderella’ in 1950, they had weathered significant change, the threat of closure and the greatest artistic and technological shift animation had seen, and in the process, refined and developed and perfected their skills as storytellers, artists and filmmakers. 'The Jungle Book' was the culmination of all their work and learning, and even in the sadness of Walt’s absence, they knew they had delivered one of their greatest films.

They did so amidst tremendous turmoil and upheaval. No matter how successful a film would be, it could not guarantee that another would follow it, and any financial failure could bring them to the edge of catastrophe. The name of Disney had also started to shift in the minds of audiences. Where it once meant prestige and artistic daring, it now stood for saccharine and safe family entertainment, and often the revolutionary developments in technology and storytelling were drowned out by criticism and public indifference. And yet, each of these eight films, in their own way crafted in the edge of a precipice, are a wonder to behold. They speak directly to the heart of the human experience, whether as a celebration of the goodness of a kind soul or tremendous bravery in the face of adversity.

Each film is connected by a unifying theme, something that would never happen again for Disney animation - the search for a place to belong. The characters of the Silver Age are seeking something, seeking who they are and where they belong in this world. The journeys may be full of song and joy and excitement, but the stakes are always at their highest. This is their power, to speak to the primal and human within us, pencils on a page showing us something about ourselves more profound than a human face or body ever could.

It was also a shift of power, from the great master himself to the great artists around him. This was the age of the Nine Old Men, the ascension of Mary Blair and Eyvind Earle, Claude Coates and Ken Anderson and Walt Peregoy. It was defined by the sounds of Oliver Wallace and George Bruns, and the songs of Richard and Robert Sherman. It would see the Inking and Painting department rise to the greatest in the world, before coming to a crashing end, and the one of the most seismic shifts in the history of the medium, where a photocopier took their place. Walt Disney may have had his name above the title and been the face of the company, but it was these figures and hundreds of others that were the true artists of the Silver Age. These films were their labours of love, and often hard won. They committed their minds, bodies and souls to them, and often their minds, bodies and souls would suffer, but each film was crafted with one intention - to make the best film they possibly could, a film they could look back on with pride. It was 17 years of sprints, stumbles, falls, successes, failures, fury, passion, disappointment, confusion, frustration, terror and blind faith, and looked back now with the hindsight of decades, seventeen years of unbroken success the likes of which Walt Disney Productions had never experienced, and arguably never would again.

And at its centre, the face and voice of the company, was a man who can become one of the defining figures and architects of American culture. His determination, uncompromising standards, imagination and stubbornness had manifested into one of the most successful entertainment companies in the world, expanding out of the cinema screens into television, and finally writ large in brick and mortar so that audiences could not just watch a Disney production, but be in one.

But as 1967 came to a close, the future for the company was terrifyingly uncertain. They had faced uncertainty before, more often than not over their financial prospects, but this was different. They had lost their leader, a man who, even when he was ambivalent, still somehow managed to influence every movement of his company. Walt Disney Productions had been built on the foundation that was Walter Elias Disney. But with Walter Elias Disney gone, who on earth were they? Nowhere was this felt more acutely than the animation department. They knew they were prepared for the chopping block. In one way or another, they had been since the 1940s, but Walt had always held disaster at bay, often out of stubborn loyalty. That protection was now gone. They were now going to have to defend themselves.

In the last month of his life, Walt Disney was visited by Wolfgang Reitherman in hospital. Even though he was keeping his illness a secret, the future weighed on his mind. He made a request to Reitherman, that if anything should happen to him, Wollie would lead the animation department, making sure they survived. Reitherman had promised he would. Besides, they were already at work on a new film, a rare original idea, a jazz-infused story of a family of cats living in Paris. He never expected that, very soon, he would have to fulfil that promise.

The next 20 years would be the most tumultuous in the history of Disney animation. Those that had answered to Walt Disney were now left to lead the department without him, his shadow looming over every decision they would make. The films they would produce in this period would bear the weight of their mourning and uncertainty, and the scars of a department slowly being phased out of existence. They would weather the shattering of morale and relationships, an indifferent audience, the transition from a company to a corporation, and rivals that would push them to the brink of box office disaster. And yet, these eight films would hold Disney animation in place, not buckle under the weight. A few would even end up being classics in their own right. And in the process, they would lead them through the darkness towards the light ahead. From 1970 to 1988, Walt Disney animation would find its feet in a world without Walt Disney, and begin to find a voice again.

Walt Disney Animation was entering its Bronze Age.

- ‘The Jungle Book’ made its home entertainment debut on VHS in the US in May 1991 as part of the Walt Disney Classics line. It sold 7.4 million units, making it the third most successful VHS release after ‘Fantasia’ and ‘Home Alone’. A Laserdisc version was released the following year.

- For its 30th anniversary, the film was re-released on VHS as part of the Walt Disney Masterpieces line in October 1997, featuring a new restoration and making-of featurette.

- The film made its DVD debut as part of the first-run line of limited DVD released in December 1999.

- The film was released on DVD in October 2007 as part of the Platinum Edition line for its 40th anniversary. The two-disc set featured a new digital restoration and a healthy selection of bonus features, including making-of documentaries, archival material, deleted songs and reconstructed sequences from Bill Peet’s treatment. It went into moratorium in 2010.

- In February 2014, the film made its Blu-ray debut as part of the Diamond Edition line, carrying over most of the material from the Platinum Edition DVD, along with a small selection of new features.

- While the film is still easily available on Blu-ray in other countries, the Diamond Edition release, along with the accompanying DVD, were placed in moratorium in January 2017.

- The film is available on Disney+.

- Wikipedia on 'The Jungle Book' (the first book, the second book and the film), Rudyard Kipling, Ollie Johnston and Walt Disney.

- The Jungle Book: Diamond Edition, Blu-ray, 2014

- The Walt Disney Film Archives: The Animated Films 1921 -1968, ed. Daniel Kothenschulte, 2016

- Walt Disney: The Triumph of the American Imagination, Neal Gabler, 2006

- Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, Mindy Johnson, 2017

- The Disney Studio Story, Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, 1988

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume IV - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Mid-Century Period (The 1950’s and 1960’s), Didier Ghez, 2016

- The Archive Series: Nine Old Men - The Flipbooks, Pete Docter, 2012