Music ∷ Sam Porter

Show Artwork ∷ Nikolaos Pirounakis

Episode Artwork ∷ Lily Meek

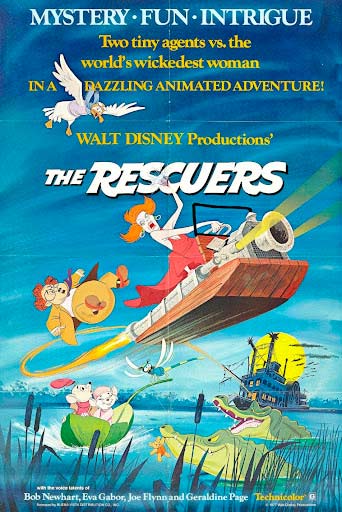

Where ‘Winnie the Pooh’ had been the work of the great masters, ‘The Rescuers’ was the first true collaboration between the remaining Nine Old Men and the new generation of animators intended to take over, no longer just in-betweeners and assistant animators but strong and clear artistic voices with new ideas and fresh approaches. This new film did not possess quite the same familiar warmth and texture. The year 1977 was a turning point for American cinema with the release of ‘Star Wars’, but for Disney animation, it was also a transition from the Disney of the past to the potential Disney of the future, the gulf between the two mirrored in the impossible journey of two intrepid little mice on a mission of rescue and redemption.

But if the three of us work together and we have a little faith...

At a meeting of the Rescue Aid Society, a consortium of mice attached to the United Nations, a bottle with a note inside is opened with a message from a little girl named Penny (Michelle Stacy) asking for help. The Hungarian representative Miss Bianca (Eva Gabor) volunteers for the case, and chooses the quiet and bumbling janitor Bernard (Bob Newhart) as her co-agent. After following a series of clues to a children’s orphanage, and with the help of the orphanage cat Rufus (John McIntire) and an albatross named Orville (Jim Jordan), Bianca and Bernard track Penny down to the Devil’s Bayou, where she has been kidnapped by the maniacal Madame Medusa (Geraldine Page) and her hapless accomplice Mr Snoops (Joe Flynn). The pair force Penny to crawl into a submerged pirates cave to find the legendary diamond, the Devil’s Eye, so with the help of the local swamp animals, Bianca and Bernard stage a rescue, finally outwitting Medusa and her pet crocodiles Brutus and Nero. With the diamond safely smuggled away, the mice help Penny return to the orphanage, where she is finally adopted by a loving family.

As credited in the opening titles, ‘The Rescuers’ is “suggested” rather than based on the series of children’s books by British writer Margery Sharp, specifically the first two volumes - ‘The Rescuers’, published in 1959, and ‘Miss Bianca’, published in 1962. Sharp was a successful author and playwright, with a number of her books adapted for the screen in Hollywood in the 1940s. ‘The Rescuers’, which told the story of a team of mice from the Prisoners’ Aid Society rescuing a Norwegian poet imprisoned in a European castle in the 1950s, had originally been intended for adults, but had proven unexpectedly popular with children.

It was a departure from Sharp’s previous work, and critics found the book ingenious and charming, with a writer in ‘Kirkus Reviews’ remarking that it was “a tale made to order for Walt Disney”. The book was illustrated by Garth Williams, who had also illustrated E.B. White’s classic children’s books ‘Charlotte’s Web’ and ‘Stuart Little’. Over the following twenty years, Sharp would write a further eight books in the series, the final volume ‘Bernard into Battle’ published in 1978.

In the early 1960s, Disney purchased the rights to the books, and in 1962 work began to develop them into a feature. In January 1963, Otto Englander submitted an outline, retaining the plot from the first book involving the rescue of the Norwegian poet from a European totalitarian state. The following year, story artist Joe Rinaldi developed Englander’s treatment through storyboards, but Walt became uncomfortable with its political overtones and shelved the project. Following Walt’s death, Englander returned to Sharp’s novels, this time developing a narrative set in the Middle Ages where the mice rescue Richard the Lionheart. With ‘Robin Hood’ placed in development soon after, the project was once again shelved. What had become clear was that, despite the charming premise of the novels, the stories in their current state did not immediately lend themselves to screen adaptation.

A few years later, Margery Sharp’s books caught the attention of the artists brought to Disney through the Talent Development Program, particularly an ambitious, charismatic and talented animator named Don Bluth. The story would still go through numerous iterations before what we now see in the final film, but the combination of tradition and innovation now buzzing through the corridors of the animation department would quickly elevate the project, driving Disney animation into new and uncharted territory.

Another that had begun development in 1971 was an adaptation of Paul Gallico’s novel ‘Scruffy’, the story of a family of barbary macaques, a monkey species native to the island of Gibraltar. In Gallico’s novel, the family and its leader Scruffy are under threat from the Nazis, who are attempting to capture them. The project seemed an odd fit for Disney, but the film was in active development for a number of years, with Anderson creating a vibrant and dynamic series of artworks that suggest a much more colourful story than one would expect.

In the meantime, ‘The Rescuers’ was still in development, though no one had taken enough of an interest to move the project along. With the success of ‘Robin Hood’, the new artists being developed through the in-house Talent Development Program were keen to work on a project of their own. Many of them had been working animators before being admitted into the program, and impatient to take more responsibility at Disney. Chief among them was Don Bluth, one of the more experienced artists on the program.

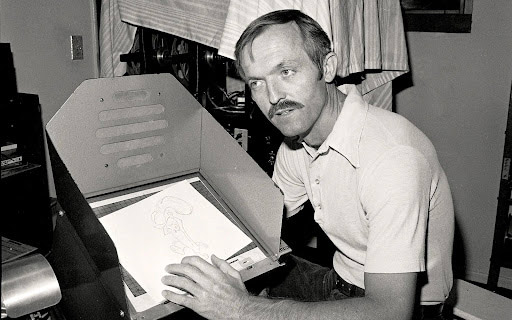

Don Bluth was born in El Paso, Texas on September 13, 1937, the son of Emaline and Virgil Ronceal Bluth. Born only a few months before the release of ‘Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs’, Bluth was part of the first generation to grow up on the Disney animated features, and as a child, would ride his horse to the nearest movie theatre to watch Disney films. The family moved between Utah and California, with Bluth attending Brigham Young University in Utah for a year, but in 1955 he began work at Disney as an in-betweener for John Lounsbery on ‘Sleeping Beauty’.

Two years later, Bluth left Disney and spent the following years on a mission in Argentina for The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, and upon returning to the United States, completed his studies at Brigham Young University with a degree in English literature. In 1967, he turned his attention back to animation by joining the production company Filmation Associates, and in 1971 returned to Disney as part of the Talent Development Program.

Having been raised on and inspired by Disney animation, Bluth had strong beliefs in the integrity of the early animated classics, and along with many of the artists in the program, longed to return the form to that past technical glory. He began to look around for potential projects he could spearhead, and came upon the languishing ‘Rescuers’. It was decided that the film would be a ‘B’ project for the new artists to work on, with a smaller budget and simpler animation, while the core team continued with the ‘A’ project, likely the adaptation of ‘Scruffy’.

Development on ‘The Rescuers’ recommenced in earnest in 1972, with plans to adapt Marjory Sharp’s most recent novel in the series, ‘Miss Bianca in the Antarctic’. In the novel, a polar bear is captured and forced to perform by a group of penguins. Desperate for help, he sends a note in a bottle that is intercepted by the Prisoners’ Aid Society. Jazz singer Louis Prima had been disappointed about not being cast in ‘Robin Hood’, even going so far as to record a concept album combining songs of his own with those from the film, so for ‘The Rescuers’, Prima was approached to voice the polar bear, now named Louis. A number of songs were written for the project by Floyd Huddleston, many of which were recorded in demos by Prima. However, in 1975, Prima was diagnosed with a brain stem tumour, and this version of ‘The Rescuers’ was scrapped. Prima passed away in 1978.

Around the same time, development on ‘Scruffy’ came to a halt, and it was decided to shelve the project. The senior animators now needed a new project, but while Anderson was still busily working on characters and ideas for ‘Catfish Bend’, it wasn’t in the necessary shape to enter production. As the Louis Prima version of ‘The Rescuers’ was shut down, Wolfgang Reitherman and the core animation team turned their attention to that film and decided to elevate it to a major production, taking the place of ‘Scruffy’.

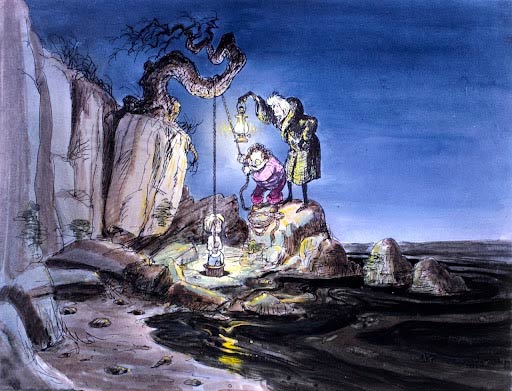

The first decision was to scrap the Antarctic storyline completely, since the setting wasn’t dynamic enough for a feature film. This brought the team back to the same problem - they didn’t have a story and they didn’t have a strong enough villain. Larry Clemons, Reitherman and Anderson returned to Sharp’s books for further inspiration. For the narrative itself, they looked to the second book in the series, ‘Miss Bianca’. In this book, Bianca is sent on a mission to rescue an orphaned girl named Patience from the clutches of the wicked Grand Duchess, living in the Diamond Palace.

“I remember I went to Europe…” recalled Wolfgang Reitherman, “I took Margery Sharp’s books along and there was in there a mean woman in a crystal palace. When I got back I called some of the guys together and said, ‘We’ve got to get a villain in this thing.’ I mean, a real honest to goodness villain.”

At some point, it was decided to borrow the device of the message in the bottle from ‘Miss Bianca in the Antarctic’, and to also shift the setting to the Deep South, the same environment Anderson was exploring for ‘Catfish Bend’ and had wanted to use for ‘Robin Hood’. Many of the characters Anderson had developed for ‘Catfish Bend’ were now transferred over to ‘The Rescuers’ to populate the swamps around the Devil’s Bayou.

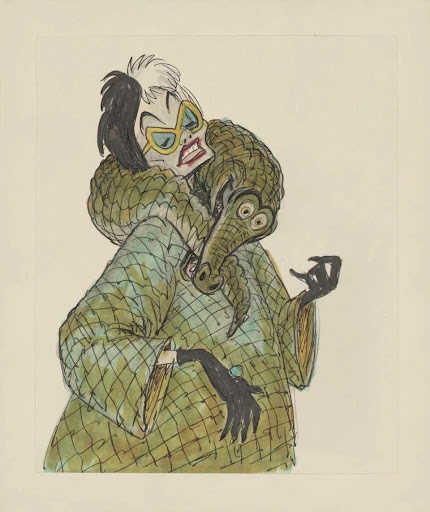

On the issue of the villain, Ken Anderson proposed something unexpected - what if the villain was Cruella De Vil? The maniacal socialite had been an enormous success in ‘One Hundred and One Dalmatians’, and seemed to fit all the requirements for ‘The Rescuers’. Rather than being immediately dismissed, the idea was taken seriously, with a series of character sketches of Cruella completed, now updated for the 70s with a more contemporary look and a love for crocodile skin rather than fur.

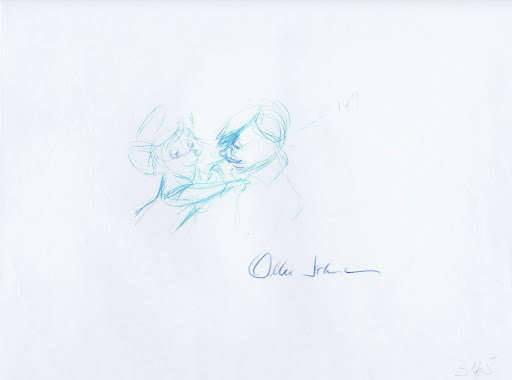

There was significant opposition to the idea. Ollie Johnston didn’t see the logic in developing the film as a pseudo-sequel to ‘Dalmatians’, and Milt Kahl felt uncomfortable taking on the character that was now considered the masterwork of fellow animator Marc Davis. The idea was eventually scrapped, but it was enough to spark inspiration for the film’s final villain, the maniacal Madame Medusa.

There were still a number of character and story issues to be solved, but ‘The Rescuers’ was now on its way to being Disney’s next animated feature. Wolfgang Reitherman would once again take directing duties, along with John Lounsbery. The team of directing animators would include, as always, Frank Thomas, Ollie Johnston and Milt Kahl, but rounding out the team was Don Bluth. It was the first time one of the new animators had been promoted to such a senior position within a production, and the first time in many, many years where the core directing team wasn’t limited to just members of the Nine Old Men. It was a significant vote of confidence in Bluth and his skills, but would also bring the past and future of Disney animation into conflict with one another.

The making of ‘The Rescuers’ did not suffer the kinds of drama that had plagued almost every feature project that came before it, but it wasn’t without its tensions. The Nine Old Men, especially Wolfgang Reitherman, saw it as their job to maintain the philosophies they had developed while shepherding Disney through the loss of Walt. They still strove for the best work possible, but with consideration for the practical and financial limitations. The United States was in the middle of a recession, and while Walt Disney Productions was still making a significant yearly profit, the animation department consumed significant resources and took far longer than other departments to produce a product. Reitherman was determined to control costs, and part of his plan with the new artists being trained in the Talent Development Program, as well as the newly-established Character Animation Program at CalArts, was to foster artists who could adhere to these requirements.

What he hadn’t banked on was that this generation had grown up on Disney animation at its artistic height, and were expecting to be working on projects with the pedigree of ‘Snow White’ and ‘Pinocchio’, not ‘The Aristocats’ or ‘The Jungle Book’. A brochure for the Talent Development Program distributed in the late 70s encouraged “people who are attracted to the Disney style and tradition of animated storytelling” to apply, “to create new worlds of believable fantasy and a new generation of colour Disney characters”. Reitherman and his team had shifted the focus from technical artistry to character animation, focusing on performance and personality rather than lush artwork and textures. This had played to their strengths - they didn’t have Walt’s ability with story and structure, but they knew how to develop strong, arresting characters.

Don Bluth in particular pushed against Reitherman’s approach, favouring draftsmanship and stronger storytelling that would take more time and more money, but would achieve greater results, an approach supported by a number of the artists who had joined through the in-house program. Reitherman also pushed for further recycling of classic animation, a technique that had become standard practice at Disney under his leadership but continued to frustrate even the animation veterans, with Milt Kahl in particular vocal in his objections to reusing animation from ‘Snow White’ and ‘Bambi’ in the film.

By the time ‘The Rescuers’ entered production, many of the story problems had been solved. There had been talk of making Bianca and Bernard a married couple, but it was decided that the film would benefit from romantic tension between the two mice. Bouncing off from the idea of reusing Cruella DeVil, a new villain had emerged in Madame Medusa, featuring a wickedly funny voice performance by acclaimed actor Geraldine Page and beautifully animated by Milt Kahl, who considered Medusa the best character he had worked on. His intention had been to create a villain to rival Marc Davis’ work with Cruella. For the rescuers’ transport, a pigeon had been suggested, but Ollie Johnston recalled footage from a ‘True-Life Adventure’ episode showing the ungainly manner of an albatross’ take-off and landing and thought that an albatross would offer greater comic potential. Johnston would do stellar work with the character, named Orville after one of the Wright Brothers.

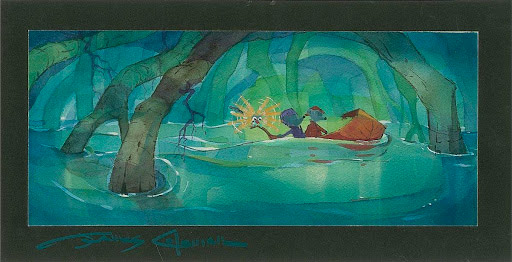

Another minor character soon became a highlight of the film, a member of the Devil’s Bayou volunteer brigade that was not a part of Ken Anderson’s initial collection of characters from ‘Catfish Bend’. Anderson had been inspired by the dragonflies he had seen while fishing in Lake Sherwood, and chose the insect to ferry Bianca and Bernard around the swamp, giving the character the name Evinrude as a joke. The animators quickly saw the comic potential in the character, deciding he should communicate through sound rather than dialogue. Veteran sound designer Jim Macdonald was brought out of retirement to work on the character. He began by exploring the sound of a buzz saw, but instead created a device that used a piece of brass tubing and an air hose, along with a rubber membrane fashioned as a drum that he could play. He then added his own panting and wheezing to make the character more believable.

For the music in the film, Disney initially approached the beloved songwriting team the Carpenters, but due to scheduling conflicts, they were unable to commit to the project. Disney veteran Sammy Fain had also been asked to provide songs for the film, but in the end, the task fell to Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins. They composed three songs for the film, including the haunting opening song 'The Journey', but Reitherman was still very fond of one of Fain’s songs, "The Need to Be Loved". He asked Connors and Robbins to write new lyrics to Fain’s melody, and the result, 'Someone’s Waiting For You', replaced one of their original songs in the final film. All three songs were performed by American singer Shelby Flint, and would add a very different dimension to the film. For the first time since ‘Bambi’, the songs were not part of the action of the film or sung by characters within it (with the exception of 'The Rescue Aid Society'), instead commenting on the action and themes of the film. For the score, another external artist was approached, American songwriter and composer Artie Butler. His intention was for the score to give a sense of enormity and helplessness to Bianca and Bernard’s journey.

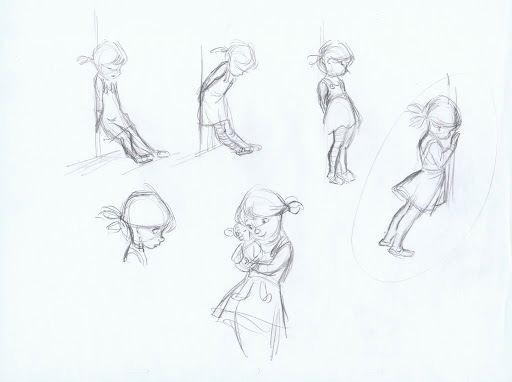

“In ‘The Rescuers’, the little girl had to be drawn sincerely because she was the heart of the story; Medusa and Snoops could be wild, comic figures because they were not sinister.” - Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, ‘The Illusion of Life’

At the centre of the film was Penny, the little girl kidnapped from an orphanage by Madame Medusa. The emotional integrity of the film rested on the success of this character, and involved careful consideration from all departments. Her voice was provided by actor Michelle Stacy, and Milt Kahl and Ollie Johnston used Stacy as a visual reference for the character. A number of ideas were explored for her introduction in the film, including a sequence where she performed for prospective parents, but story artists Vance Gerry and Larry Clemons pushed for a simpler approach. A sequence was developed between Penny and the orphanage cat Ruphus, a self-caricature of Ollie Johnston. The sequence would be one of the quietest and emotionally potent in any Disney film until that point. “Now, the little girl was so believable”, Reitherman later remarked. “All those things around her were great, but you needed that sincerity.”

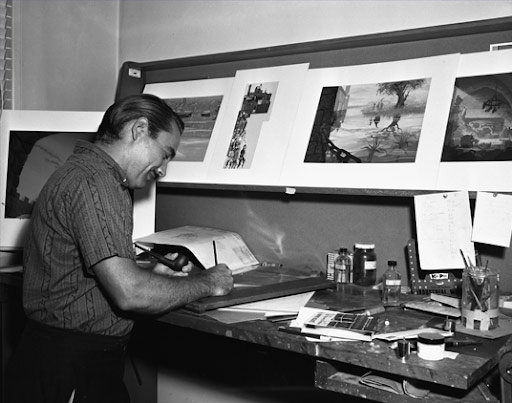

During production on ‘The Rescuers’, one of the artists who had been fundamental to developing the look of Disney with the introduction of Xerox was asked to return to the studio. Walt Peregoy had left Disney in 1965 after his relationship with Walt had become difficult and had since been working in part for Hanna-Barbera. In 1974, Ken Anderson and Wolfgang Reitherman approached Peregoy with the role of Head of the Background Department on ‘The Rescuers’, and while Peregoy’s relationship with Reitherman had also been fraught, especially during production on ‘The Sword in the Stone’, he agreed to return.

Almost immediately, Peregoy and Reitherman began to clash again over the same artistic differences. Peregoy pushed for a more dynamic graphic style, while Reitherman demanded the traditional Disney look. Peregoy eventually left the film, asking that his name be removed from the credits, and artist Al Dempster was brought out of retirement to help finish the backgrounds. Peregoy would remain at Disney though, working on the development of EPCOT at Walt Disney World.

The Xerox process went through another important evolution during the making of the film. The process now allowed for grey lines rather than black, softening the harshness of the animation lines. It was such a significant change that many critics assumed the studio had adopted a whole new style of animation.

During production, The Rescuers was hit with two significant losses. John Lounsbery, one of the Nine Old Men who had been at Disney since 1935, had recently been promoted to director with the Oscar-nominated short ‘Winnie the Pooh and Tigger Too’ (1974). ‘The Rescuers’ was the first feature on which he would direct, but during production on the 13th of February 1976, over a year before the film would be released, John Lounsbery passed away. He was the first loss within the ranks of the Nine Old Men, and a significant voice within both the film and the department. His directing duties on the film were handed to veteran animator Art Stevens, who had been with the studio since 1939.

Another unexpected loss was beloved American actor Joe Flynn, who was the voice of Madame Medusa’s henchman Mr Snoops. Joe Flynn, best known for his role as Capt. Wallace B. Binghamton in the television series ‘McHale’s Navy’, had also appeared in a number of live-action Disney films. On July 19, 1974, three years before the release of the film, Flynn was found in the family swimming pool, having suffered a heart attack while swimming. During production, there was talk of expanding Mr Snoops’ role within the film, but in the end it was decided to contain the performance to only those lines Flynn had recorded for the film before he passed away.

ANIMATION: The film was the first production for future animation greats Glen Keane and Ron Clements.

ANIMATION: Jane Baer, who like Bluth had been an in-betweener on ‘Sleeping Beauty’, also returned to Disney to work on ‘The Rescuers’. “One of the differences I noted when I came back,” she later recalled, “they were more encouraging towards women.” She would later form her own animation house with husband Dale Baer.

ANIMATION: For the well sequence, there were concerns it would be too frightening, so rather than casting shadows from the lanterns, the walls were painted in dark colours and made to look wet, while the shoes and feet of the characters were painted dark to give the illusion of shadows.

VOCAL PERFORMANCE: Actor Jeanette Nolan gave an unexpected dimensionality and comedy in her voice performance as muskrat Ellie Mae, which excited the animators. Through development and continuity on the final film, most of this quality was removed.

After three years in production, with over 105,000 cels and 750 backgrounds completed, ‘The Rescuers’ opened on June 22, 1977. The film is now thought of as a minor film in the Disney canon, but upon release, ‘The Rescuers’ was an enormous critical and commercial hit, many critics calling the best film Disney had produced of any kind in over a decade. Writing in the ‘Los Angeles Times’ on the 3rd of July 1977, critic Charles Champlin called the film “the funniest, the most inventive, the least self-conscious, the most coherent, and moving from start to finish, and probably most important of all, it is also the most touching in that unique way fantasy has of carrying vibrations of real life and real feelings.” On June 15, ‘Variety’ called it “the best work by Disney animators in many years, restoring the craft to its former glories. In addition, it has a more adventurous approach to color and background stylization than previous Disney efforts have displayed, with a delicate pastel palette used to wide-ranging effect.”

The film had cost $7.5 million to produce, but in its initial box office run grossed $16.3 million in the United States. It was also an enormous hit worldwide, earning $48 million at the global box office. In France, the film even outgrossed ‘Star Wars’ and was the biggest hit of the year in West Germany. Its remarkable critical and commercial run reached its peak with an Oscar nomination for Best Original Song with “Someone’s Waiting For You”, the Sammy Fain song that Wolfgang Reitherman has asked Carol Connors and Ayn Robbins to write new lyrics for. When ‘The Rescuers’ returned to cinemas in 1983, it was once again a major box office hit, earning $21 million domestically. Six years later, in 1989, it would do the same numbers again.

An unexpected chapter in the legacy of ‘The Rescuers’ came in 1999 with the second VHS release. Only days after the film was released, Disney recalled 3.4 million VHS copies of the film after the image of a nude woman was discovered in the background of a shot as Bianca and Bernard flew through New York City. Barely noticed in the theatrical runs, the image appeared to have been inserted in the film during post-production, though Disney has never said how it ended up in the film or who placed it there. Two months later, the film was re-released on VHS with the image removed.

The emotional resonance and darker tone we see in ‘The Rescuers’ may seem relatively standard now for Disney feature animation, but seen within the context of the films that came before it, there is something quietly revelatory about the maturity of the film. Disney had rarely given their films this much space to breathe or aimed for this level of emotional integrity, especially around Penny’s delicately handled feelings of loneliness and abandonment. ‘The Rescuers’ is a quiet, deeply felt film that still lands with an unexpected emotional power, but a power that is carefully earned. That it hasn’t endured as strongly as its contemporaries is understandable - it doesn’t have any big musical numbers or broad characters - but it is also understandable that it would have connected with audiences in 1977 with the political and social unrest of that decade. ‘The Rescuers’ is a film that engages with your heart, built on a foundation of human experience and emotions. In many ways, it brings the continuing theme of Disney feature animation (lost children, abandonment, found family, salvation) to a new level of maturity. It isn’t without its flaws, but perhaps more so than any film in the Bronze Age, haunts you long after it is over.

‘The Rescuers’ had proven to be an unexpected hit for Walt Disney Productions, raising their revenue in 1977 by 29 percent. For critics and audiences, it seemed that Disney had entered a new golden era for animation, emerging from the shadow of Walt Disney. There was even talk of developing a sequel to the film, something Disney animation had never done before. It was a tremendous vote of confidence in the leadership of Wolfgang Reitherman and the Nine Old Men, but the future they had feared was starting to come to pass. John Lounsbery was gone, Ward Kimball had moved to television and since retired, Marc Davis had long moved to Imagineering and Eric Larson was focused on teaching and mentoring. Only Reitherman, Thomas, Kahl, Johnston and Les Clark remained, and Clark would pass away only a year later. The guardians of Disney animation were getting too old to keep going, and were going to have to rely on the rising stars of the studio to take over.

Chief among them was Don Bluth. ‘The Rescuers’ represents a turning point in his career. Though he would share authorship over the film with many others, elements of it suggest the kind of filmmaker he would become - detailed, melancholy, lush, romantic and uncompromising. He had risen quickly within the company, and had been given the responsibility of directing the prestige short The Small One (1978), a story based partly on the Nativity. It was assumed that Bluth was being prepared as Wolfgang Reitherman’s successor.

For Bluth though, the experience of making ‘The Rescuers’ was deeply frustrating. He had tried to push the film towards a more interesting aesthetic, but had experienced pushback at every turn. His work on the film and those of his fellow artists had been praised by critics, but despite the promotion of this new generation of Disney artists in the publicity, none had been mentioned by name.

During production on ‘The Rescuers’, Bluth had noticed that the whites in the eyes of the characters hadn’t been coloured in. When he asked why, he was told it was too expensive and too time-consuming. Bluth and his friend and fellow animator Gary Goldman took it upon themselves to test how expensive it would be, finding their own equipment and working on a sequence. They discovered a cost-effective way of coloring the whites in the eyes, but when they reported their findings back to the senior animators, they were told to follow orders and stay in line. Many years later, both Bluth and Goldman would cite this incident as “the straw that broke the camel’s back”. Their relationship with Disney was about to become unbearable, and the next Disney animated feature, an unassuming and charming story of a fox and a hound dog navigating a forbidden friendship, would very soon become a battle that would once again push Disney animation to the edge.

- The first home video release for ‘The Rescuers’ came with a VHS release of the film in the UK in March 1991.

- In September 1992, ‘The Rescuers’ made its VHS and Laserdisc debut in the US as part of the Walt Disney Classics line.

- The film returned to VHS in January 1999 as part of the Walt Disney Masterpiece collection, but was recalled three days later when an image of a naked woman was found in the background of a sequence. The re-edited version was released in March.

- ‘The Rescuers’ made its DVD debut in May 2003, along with a new VHS release. Bonus features included interactive games and a selection of Disney shorts.

- When the Diamond Edition Blu-ray line was launched in 2009, ‘The Rescuers’ was considered for inclusion as the film to represent Disney animation in the 1970s. These plans were later scrapped, and the film made its Blu-ray debut as part of a 2-movie collection with its sequel ‘The Rescuers Down Under’ in August 2012.

- The film is available on Disney+.

- Wikipedia on The Rescuers (the book and the film), Margery Sharp, Don Bluth, Ben Lucien Burman, and a list of unproduced Disney animated shorts and feature films.

- The Disney Studio Story, Richard Hollis and Brian Sibley, 1988

- They Drew As They Pleased: Volume V - The Hidden Art of Disney’s Early Renaissance (The 1970s and 1980s), Didier Ghez, 2019

- Ink & Paint: The Women of Walt Disney’s Animation, Mindy Johnson, 2017

- Disney Animation: The Illusion of Life (Popular Edition), Frank Thomas and Ollie Johnston, 1984

- The Traditional Animation Show - Don Bluth & Gary Goldman, Traditional Animation, 18th September 2021

- IMDB entry for The Rescuers